Eric Schlosser sat unassumingly — and almost out of place — in a floral armchair in a spacious, elegantly decorated suite on the 10th floor of Seattle’s Fairmont Olympic Hotel. Behind him, a poster rested on an easel. It featured a juicy burger, bigger than Schlosser’s head, adorned with an American flag.

In many ways, the jumbo burger is a metaphor for Schlosser’s life over the last decade or so — the fast-food industry looming large as he researched the modern American convenience-based food system, first publishing his findings in a two–part article in Rolling Stone in 1998. The piece generated more mail than anything the magazine had run in years, and soon Schlosser, a National Magazine Award-winning journalist, was at work on a full-length exposé titled Fast Food Nation: The Dark Side of the All-American Meal.

That muckraking book — which revealed the inner workings of America’s food system and its effects on animals, land, and people, from the immigrant meatpacker to the low-wage fast-food worker to the blissfully unaware Big Mac eater — generated critical acclaim. Schlosser went on to apply his investigative skills to a book on America’s black market and, earlier this year, Chew on This, a revamped version of Fast Food Nation aimed at younger audiences.

“The first step is to just open your eyes and see what’s happening, and I think a lot of my work is driven by that aim,” he says. In addition to opening consumers’ eyes, Schlosser’s work has hit its target: earlier this year, 19 food-industry associations launched Bestfoodnation.com, a public-relations campaign that, among other things, accuses Schlosser of publishing misinformation. But Schlosser stands by his facts, and has said that he would jump at the chance to actually speak to a representative from McDonald’s. (The chain has refused to speak to him even off the record.)

Amiable and intelligent, Schlosser is now touring in support of the Fast Food Nation film, a fictional narrative based loosely on the book and directed by Richard Linklater. Schlosser and Linklater collaborated throughout the process, from planning sessions to screenplay drafts to shoots with the big names (Bruce Willis, Greg Kinnear, Ethan Hawke, Avril Lavigne) peppering the film’s cast. The result is an almost shockingly gruesome, but realistic, look at the fast-food industry through the eyes of the many characters (from cattle ranchers to company execs) playing a role in satisfying our appetite for a quick, cheap meal. “One of my favorite shots in the film is [an] aerial view of the feedlot, where it just goes on and on and on,” Schlosser says. “I mean, that’s insanity.”

Hungry for his thoughts on how to change the way Americans view food, I sat down with Schlosser to chat about reinvigorating a holistic, healthy food system, weaning his kids off Happy Meals, and more.

What do you hope this movie conveys about the American food system?

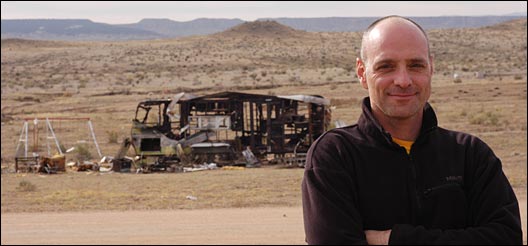

Image: © Fox Searchlight

I hope it just shows people how the system works. Most people have no idea where their food’s coming from and how it’s being made and what it’s doing to the land and what it’s doing to the animals. And most importantly for me, what it’s doing to people — in this case, the people who process and are involved in bringing you your food.

The film is really about showing you what’s happening and trying to make people think, and ideally make them feel too — feel some compassion, move them in some way.

What do you think we could do to fix the system?

The first thing to do is educate and inform yourself. And really get a sense of what’s going on. After that, it’s up to you and how passionate you feel.

There’s no shortage of groups doing really good things on different issues that are part of the problem. If you care about exploitation of poor immigrant workers, there are workers’ rights groups and immigrants’ rights groups. If you care about what we’re doing on these factory farms to the animals — which is cruel beyond belief — there’s the Humane Society and there are different groups working on behalf of animal rights.

The Sierra Club is doing a good job right now in terms of [working to mitigate] the environmental impact of factory farms. The runoff from these farms is one of the leading causes of water pollution in the United States. The hormones that they’re giving to these cattle are excreted in their manure and are winding up in streams. And they’re finding fish that are weirdly deformed — their sexual organs are deformed — downstream of these feedlots, and that’s just crazy.

The simplest thing people can do is be conscious of where they spend their money. As a consumer, you can think of each purchase as a vote. When you go to fast-food chains and buy industrial meat, you’re endorsing those practices. If you spend a little more time and money and buy food that’s being produced the right way by conscientious people, then you’re supporting a totally different system.

Now, I know you have kids. Do you let them eat Happy Meals?

Before I did the research for Fast Food Nation, I took my kids to McDonald’s. It was always really irritating because they wanted to go there for the little crap plastic toy connected to some recent Disney movie. And I’d buy them the Happy Meal and they’d sit there playing with the little toy, and the food wouldn’t get eaten, and I’d wind up eating their French fries.

So I never liked it, but once I started really investigating the industry and understanding how it operated, that was it. No more McDonald’s, no more Burger King, no more KFC. And they were bugged at first, but … they survived.

What was it like working with the well-known actors in this movie?

Each person in the film came to it with a different connection to the subject matter, but all of them did it because they really wanted to and not because they were going to get paid a lot. Bruce Willis’ typical fee is higher than the total budget of this film. He did it because he felt passionate about the subject, and he was terrific. Avril Lavigne is a vegetarian, and she felt passionate about it.

(L to R) Luis Guzman, Ana Claudia Talancón, Catalina Sandino Moreno, and Wilmer Valderrama from a scene in Fast Food Nation.

Photo: Matt Lankes/ © Fox Searchlight

Wilmer Valderrama — he was absolutely amazing. Wilmer came to the United States at 14, unable to speak a word of English. He arrived in Los Angeles and immediately was thrown into a high school where all the classes were in English. So he knew — on a personal level and on a very visceral level — what it’s like to be an immigrant, and what it’s like to feel completely out of place and forced to adapt. He didn’t walk across the desert, but he had a really powerful immigrant experience here.

Why did you decide to go with a narrative rather than a documentary?

The book came out in January of 2001, and I was immediately approached by people who wanted to do a documentary. And I thought that would have been terrific. There were things I’d seen that I thought would be very powerful [on-screen] and that my words had failed to describe accurately. But I spent about a year trying to pull it together and none of the options felt right. Most of the filmmakers were working with networks, and all of these networks, one way or another, had a relationship with the fast-food industry. Even PBS — you know McDonald’s is a big sponsor of Sesame Street. So I felt uneasy.

About a year and a half after the book came out, I was approached by Jeremy Thomas, a British, independent producer who works with some of the really great European directors — totally outside of the Hollywood system. He came to me with this idea of doing the fictional film … but I just didn’t see how it would really work. So I said I’d think about it.

In 2002, I got together with Rick Linklater, who’s one of my favorite directors, and we started talking about it. We worked on it on and off for a couple of years, but I didn’t sign off the rights to my book until it was clear to me that Rick really wanted to make this film, that he would have total creative control over the film — and that the money would be raised outside the Hollywood system.

One piece of the movie that I was surprised by is the college kids who get together and talk about, basically, this notion of “eco-terrorism,” and then try to tear down a fence and let cattle out. That wasn’t necessarily part of the book.

Well, the decision to do it as a drama was, from the very beginning, a decision to keep the title, keep the spirit and some of the subject matter [of the book], but do something totally different. So we decided the film would be about people in a small town in Colorado.

One of the storylines is about a young woman named Amber who starts out as a fast-food worker. There have been a lot of films made about a young woman’s sexual coming of age — you know, a lot of French directors are obsessed with that — and we were interested in a young woman’s political coming of age. How is it that you suddenly start opening your eyes and start thinking about the world around you? In this case, she’s starting to question things; she has an uncle who has a big impact on her, but she also hooks up with a bunch of college kids who are thinking and debating about these issues. So those scenes with the college students are really meant as part of this young woman’s growing awareness.

Can you comment at all about your involvement with the upcoming film There Will Be Blood, a treatment of Upton Sinclair’s Oil?

Yeah. That was a novel I read that I fell totally and completely in love with, and I just really connected to a lot of it. It was about the birth, in many ways, of the present American oil industry. And there was also, at the core of it, a father and son relationship that I thought was very poignant. So I contacted the estate of Upton Sinclair … and obtained the rights to the book. And I wasn’t really sure what I was going to do with it.

I was approached by Paul Thomas Anderson — who was literally the only other human being I had ever met who had read the book. He felt very passionate about the book. And Daniel Day-Lewis did as well, so they very much wanted to make this movie. And I thought, well, here’s one of the handful of really great directors of the moment and here is probably the greatest actor of my generation. So I gave the book over to them.

I’ve talked to Paul about it, and I’ve read his screenplay, but I’m not actively involved in that in the same way that I have been with Fast Food Nation. I hope it’s a great success.

Fast Food Nation is somewhat related to another Sinclair book, The Jungle. It’s an interesting connection.

This film pays homage to The Jungle, it really does. It’s similar in using meatpacking as a way to literally look at what’s happening in this country … what’s happening in the slaughterhouses is a pretty good metaphor for a lot of what’s happening right now.

How do you think food issues and Fast Food Nation relate to environmentalism?

Well, you can’t pull apart the system. You have to look at it in totality. The same system that is treating workers like they’re disposable is treating [land and] animals like they’re industrial commodities. There’s no sense of stewardship. There’s no long-term vision about what is sustainable or what’s not. This is about short-term profits, pure and simple.

If you look at the values that are much more traditional in agriculture, it’s something that’s handed down generation to generation. So there’s a long-term view, there’s a sense of stewardship because you expect your family to be there for generations. It’s just totally different from one of these agribusiness companies that, you know, if it makes more sense to plow it under and put up a shopping mall, they’ll do that.

One of the problems I have with the mainstream environmental movement is it tends to be narrowly focused on very specific problems and often isn’t concerned about human beings as part of the natural environment. I think people and animals are as much of a concern as wetlands or the environment, so I’ve really tried to encourage environmental activists to broaden their view and to include human beings and to see that this system that is polluting water is also maiming poor people. I would really encourage anyone who reads this who is an environmentalist to think about broadening the view and broadening the coalitions for change, because the one other group that you could include is consumers. There’s a connection between a system that’s poisoning the land and really sickening the people who eat the food.

As consumers, should we focus on buying locally, organic, vegetarian? Should we fight the subsidies that these companies are getting, pressure companies … ?

It all sounds good. I’m not a vegetarian, but there’s no question that a vegetarian diet is much more sustainable for the land, is much more sustainable for many of the people eating that way. I eat meat, but not every day. I don’t buy industrial meat.

If I had a choice between eating produce that was local or eating produce that was organic and shipped from China, I would probably choose the local. It’s complex, but the goal is a system that is sustainable. The agro-industrial complex that we have right now — that is treating animals this way, that is treating the land this way, that is treating human beings this way — has only really been around for 30 to 35 years, and we’re already seeing huge costs in health, in terms of the environment, in terms of just cruelty. So this system isn’t sustainable.

Each one of us who eats is part of that. If you eat, you’re connected to this, and you’ve got to think about it and do something about it.