Sen. Lamar Alexander.Photo: Office of Lamar AlexanderSen. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.) is a patient politician. At age 38, he walked a thousand miles around the state of Tennessee to win support, door to door, for his successful campaign to become the state’s governor. Now, at 71, Alexander is facing another grueling slog: building political consensus around issues like energy and climate change at a time of seemingly intractable congressional gridlock.

Sen. Lamar Alexander.Photo: Office of Lamar AlexanderSen. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.) is a patient politician. At age 38, he walked a thousand miles around the state of Tennessee to win support, door to door, for his successful campaign to become the state’s governor. Now, at 71, Alexander is facing another grueling slog: building political consensus around issues like energy and climate change at a time of seemingly intractable congressional gridlock.

The senator recently announced plans to forfeit his role as Republican Conference chair, the No. 3 leadership position in the Senate, so he’ll be free to reach across the aisle and work toward bipartisan solutions. “[S]ome of us have to be willing to try to get results that include coalitions,” he said. That’s a rare sentiment at a time when the Tea Party is pushing Republican politics toward right-wing intransigence.

Alexander has bucked the party line on issues like climate change (he believes it’s human-caused), cleantech R&D (he wants to plow big money into electric cars and solar), mountaintop-removal coal mining (he opposes it), and a carbon tax (he’s at least willing to consider it, even if he’s not yet endorsing it). Still, this self-described “very Republican Republican” is right in line with the GOP in his love for nuclear power and offshore drilling. He sets himself apart from both parties with his deep-seated aversion to wind power.

I spoke with the renegade senator by phone last week about his vision for America’s energy future and the role he wants to play in shaping it.

—–

Q. You’ve decided to leave your leadership position in the Senate to spend more time working on issues you care about, energy among them. Why is energy a priority for you?

A. I find the intersection between environment and energy the most fascinating policy work I’ve done in recent years. I’ve found myself spending 40 to 50 percent of my policy time working on these issues. We are a big, hungry, power-consuming country. We use a quarter of all the electricity in the world. In order to keep our standard of living, we need a reliable supply of cheap energy, and it needs to be as clean as possible.

Q. Can you outline your specific goals for energy policy over the next two years and beyond?

A. First, I would try to swap the money we’re spending on permanent subsidies for energy and invest it instead in research. Second, I’d like to focus these funds on the most promising areas of clean energy. I’ve devised a plan for seven mini Manhattan Projects for energy independence: solar, batteries, green building, capturing carbon, fusion, making fuels from crops we don’t eat, and finding better ways to deal with nuclear fuel.

I like [Energy Secretary] Dr. Chu’s “hubs,” as he calls them, which to me are the same ideas as my mini Manhattan Projects. His “solar hub,” for instance, has the goal of getting the cost of solar down to a dollar a watt installed [PDF]. We approved in Congress a new “battery hub” for this year, with the goal of getting the cost of electric-car batteries down to a few cents per mile for driving.

Q. How much funding from subsidies do you want to funnel into clean-energy R&D?

A. I’m reviewing that right now. So far we’ve been able to identify about $20 billion a year of energy subsidies [that could go toward R&D]. I was visited recently by a group including Bill Gates and Chad Holliday that thought we ought to increase federal support for energy research from the current level of $5-6 billion a year to about $20 billion a year.

Q. What specific energy tax breaks do you want to eliminate in order to generate these R&D funds?

A. I would start with the wind subsidies. The U.S. is already committed to spending $26 billion over the next 10 years on subsidies for wind developers. That’s a complete waste of money in my book. This is a mature technology that no longer needs government support. I also believe the oil companies don’t need subsidies beyond those that other manufacturing and producing companies have.

Q. My understanding is that oil companies get lots of special subsidies. Their capital investments in things like oil-field leases and drilling equipment are taxed at less than 10 percent, for instance, compared to the 25 percent businesses in general get taxed.

A. Well, many of the tax credits that President Obama talks about taking away from the oil companies appear to be tax credits that any company has. My feeling is, let’s let the oil companies have the same deductions as any old company — they are entitled to whatever Microsoft and Starbucks get. Beyond that, the rest of the deductions should go into energy research.

Generally speaking, my thinking has evolved to the point where if I had a dollar, I’d first put it into research and, in certain cases, jump-starting new technologies like modular nuclear reactors [with short-term subsidies]. I would not put that dollar into any subsidy that lasts more than three to five years.

Q. With so many Republicans wanting to cut spending no matter what and maintain subsidies for fossil fuels, how will you find the political will to amp up investment in cleantech R&D?

A. That’s what the political process is all about. I’m going to be the voice that says, “Let’s not let runaway spending get in the way of what we need to do for national defense and national laboratories and national research that are an important part of a pro-growth policy for our country.”

Q. The 2009 stimulus bill targeted funding for cleantech development. Was it a success in your mind?

A. To the extent that it funded research in those seven areas of clean energy I support, nuclear and so on.

Q. You’ve said that wind is a mature technology and no longer needs government support, but that nuclear does need subsidies. Isn’t the nuclear industry even more mature than the wind industry?

A. That’s a very good point. The exception to that would be the small modular reactors of which we have none in the civilian world right now. The president has recommended a small program to jump-start small modular reactors, which I support, just as I support jump-starting electric cars. And since we haven’t built any nuclear reactors in 30 years, I’d put them in the jump-start category as well.

Q. Y

ou have said that you don’t think wind energy will help reduce our dependence on foreign oil. If we were to move vehicle transportation to electricity, wouldn’t wind be one of the power sources that could replace oil as a transportation fuel?

A. I think the idea of powering the country in any significant way on wind is the energy equivalent of going to war with sailboats. It’s a preposterous notion that makes for good TV but very poor energy policy in my view. You could string gargantuan wind farms along the Appalachian Trail from Georgia to Maine and destroy the landscape of the U.S. — that would equal the power of three nuclear reactors. And you’d still need the nuclear for when the wind doesn’t blow.

Moreover, the Department of Energy estimates that we have enough idle power in our existing plants that if we plugged our automobiles in at night, we could electrify roughly 40 percent of our cars and trucks without building one new power plant.

Q. But if we want low-carbon electric cars, we’d need to replace our grid’s high-carbon power plants with low-carbon power sources.

A. The way to come closer to that is to build 100 new nuclear plants. We’re going to have to do that anyway. About half of those would replace our existing plants over the next several years, and the other half would replace the coal plants that utilities decide are too old and dirty to put on air-pollution control equipment.

Q. Department of Energy research shows that we have enough reliable wind capacity in the central corridor and coastal areas of the U.S. to provide more than the total U.S. electricity demand, provided we find affordable power-storage technologies.

A. For now, even in the Midwest, wind turbines provide reliable power only 30 to 40 percent of the time. And it blows more at night than during the day, when we use the most electricity.

Q. At night is when we’d be plugging in our cars.

A. Again, we have all that idle electricity at night that goes unused.

It seems to me that over the next 10 years, in terms of ensuring large amounts of cheap, reliable electricity, we’ll be building a lot of gas plants, putting air-pollution controls on coal plants, looking for a way to capture carbon from coal plants, and hopefully building enough nuclear power so we can have clean electricity. Of all the renewable energies, the one with the most promise is solar, if we can get the price down to less than $1 per watt. We have rooftops for solar, and the sun shines when we need electricity most.

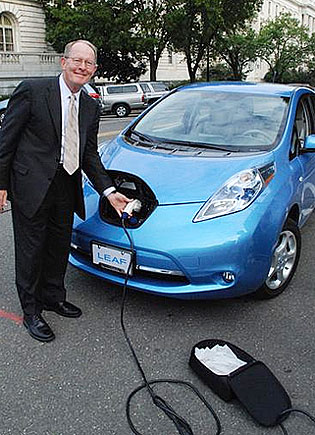

The senator charging his Nissan Leaf.Photo: Office of Lamar AlexanderQ. You are a strong advocate of electric cars. The EV bill you introduced last year sought to electrify half of America’s vehicles by 2030. Many EV advocates have argued that we can’t quickly move Americans off gas-powered vehicles unless we make gas more expensive. How do you think we can best make the shift to electric cars?

The senator charging his Nissan Leaf.Photo: Office of Lamar AlexanderQ. You are a strong advocate of electric cars. The EV bill you introduced last year sought to electrify half of America’s vehicles by 2030. Many EV advocates have argued that we can’t quickly move Americans off gas-powered vehicles unless we make gas more expensive. How do you think we can best make the shift to electric cars?

A. Making gas more expensive would be a terrible way to introduce electric cars to the country. What we’ve seen is that slight increases in the price of gas, even when it goes to $4, affects every level of economic activity. It’s the nature of our country: People are used to traveling long distances, trucks travel long distances to deliver food and other products. Our focus should be low cost, not high cost. The way to do it is to invest heavily in research, get batteries that will travel 200 to 300 miles per charge and are cheaper than they are today.

Q. Climate change is another issue you’ve led on. Many of your fellow Republicans, including presidential candidates, deny that climate change exists. Even figures like Newt Gingrich who were once outspoken on climate have backpedaled. Why are we seeing so much erosion on this issue? And what is needed to get Republicans and other skeptics to see the reality of the threat?

A. Well, it became a politicized issue. I believe that we have global warming, and I accept the conclusion of the National Academy of Sciences that human beings are a sufficient cause of it. If people of that caliber told me that my house had a good chance of burning down, I’d buy fire insurance. But I wouldn’t jump out the window or spend all my money on fire insurance.

I think what happened was the cap-and-trade proposal that came our way was such a big contraption and had so many problems that it was easily criticized. A better approach is R&D: gradually moving step by step toward cleaner forms of reliable energy.

Q. Are you saying that if moderate proposals for climate mitigation are proposed, more climate skeptics might be willing to recognize the reality of this threat?

A. Maybe in two to three years I think some of the politicizing which is on both sides will have died down a little bit. But it will be very difficult to get consensus on climate change in the next two to three years.

Q. You’ve also advocated a carbon tax on coal to address climate change.

A. I’ve thought about that. I’ve never put in carbon-tax legislation because I haven’t been persuaded by it. At some point we might require a certain limit of carbon on coal plants, just as we limit tailpipe emissions. But before we do that, we have to start with research and development to try to figure out a technological means to capture carbon.

Q. You’ve also taken a stand against mountaintop removal. What is the role of coal in America’s energy future?

A. It’s hard for me to see an energy future in our country without coal, but it has to be coal that is burned and extracted as cleanly as possible. The holy grail for electricity production is if we can find a commercially viable way to capture carbon from coal plants. If we can, coal will probably increase as a source of supply because we have so much of it.

Q. You’ve said that plugging in your new Nissan Leaf gives you “the patriotic pleasure of not sending money overseas to people who are trying to blow us up.” How are you liking your new ride?

A. I got it in May, after driving a plug-in Prius for two years, which had an A123 battery installed in it. I drive the Leaf around D.C. and have absolutely no problems — even driving it out to Dulles [Airport] and back. I don’t have a charger; I just plug it into the wall at night and that works fine.

Q. Do you get applause from bystanders as you roll silently down the streets of D.C.?

A. Not yet. They probably know I’m in the Congress, so they withhold the applause.