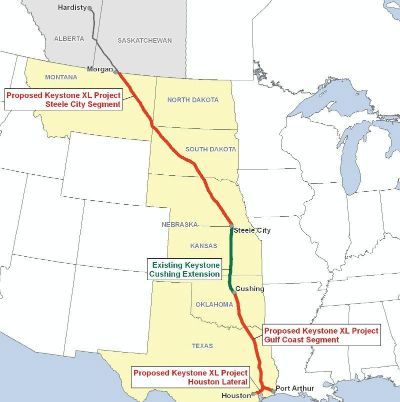

Route of proposed Keystone XL pipeline.The proposed Keystone XL pipeline — which would carry unstable, corrosive, goopy, hard-to-clean-up bitumen right down the middle of the country — could be a tempting target for terrorists. That’s one of the points I make in a new “Room for Debate” post on the New York Times website.

Route of proposed Keystone XL pipeline.The proposed Keystone XL pipeline — which would carry unstable, corrosive, goopy, hard-to-clean-up bitumen right down the middle of the country — could be a tempting target for terrorists. That’s one of the points I make in a new “Room for Debate” post on the New York Times website.

Pipeline sabotage has become a terrorist “weapon of choice,” wrote Gal Luft, executive director of the Institute for the Analysis of Global Security, in Pipeline & Gas Journal in 2005. In the post-9/11 world, he wrote, “terrorist groups have identified the world’s energy system, ‘the provision line and the feeding to the artery of the life of the crusader nation,’ in the words of al Qaeda, as the Achilles heel of the West.” Luft was warning about sabotage in Iraq and other international hotspots, but we’d be wise to consider the dangers within our own borders as well. As the Checks and Balances Project wrote recently, “It’s hard to think of a larger target for our enemies to take aim at than a 1,661-mile pipeline measuring 36 inches thick and filled with flammable crude oil.”

[UPDATE, Oct. 6, 2011: A few readers have pointed out, rightly, that there are already thousands of miles of oil and gas pipelines crisscrossing the country that could serve as targets if terrorists were inclined to attack our energy system — plus 104 nuclear reactors, more than 100 oil refineries, and a number of nuke-waste storage sites, transmission-grid connector points, etc. Keystone XL would be just one more (albeit high-profile) weak point in an already weak system.

The broader point is that our current energy system as a whole is disturbingly vulnerable to attack or sabotage or mishap. When you’re dealing with fossil fuels and nuclear power, you don’t even need a terrorist to create a terrible mess — just think of Fukushima, or the BP oil spill, or the coal-slurry disaster in Tennessee in 2008, or so many other dirty and deadly accidents. This is yet one more great reason to shift to a clean, efficient, distributed energy system — it would be much more safe and resilient. A wind farm doesn’t make a very tempting target. Big solar projects might go awry, but don’t spill oil or coal slurry when they do. Solar panels distributed on rooftops across the country would be even more resilient — knock some out of commission, but the rest keep working. And efficiency is the safest energy source of all; power sources that we don’t have to construct can’t come under attack or go haywire. Clean energy isn’t always going to be perfectly safe, but it’s a lot less vulnerable and messy than dirty energy.]

In its latest “Room for Debate” forum, the Times asks whether oil pipelines are safer than they used to be — safe enough that we should feel fine about going forward with the Keystone XL.

Seven panelists weighed in, myself and these gentlemen:

- Mohammad Najafi, editor in chief of the Journal of Pipeline Systems Engineering and Practice

- James Goeke, research hydrogeologist and professor emeritus at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln

- Adam R. Brandt, acting assistant professor in the department of Energy Resources Engineering at Stanford University

- Najmedin Meshkati, professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Southern California

- Tim Bradner, economics columnist for The Anchorage Daily News

- Peter Tuft, engineering consultant in Australia

Here’s my “Room for Debate” contribution in full:

Forget the tree huggers. Even many red-blooded red-staters don’t trust that the Keystone XL pipeline would be safe and leak-free.

Husker football fans booed a TransCanada-sponsored video at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s Memorial Stadium on Sept. 10, spurring the school’s athletic department to drop a sponsorship deal. Nebraska’s Republican governor, Dave Heineman, is calling on the Obama administration to deny a permit for the project; the state’s senators, one Republican and one Democrat, oppose it, too. And in a State Department hearing in Lincoln, Neb., on Sept. 27, about 80 percent of the 1,000-plus citizens in attendance were opposed to the pipeline — despite the fact that pipeline boosters bused in sympathetic crowds from other states.

A big worry is that the pipeline’s proposed route through Nebraska would cross about 250 miles of the Ogallala Aquifer, the nation’s largest underground source for drinking water and crop irrigation. Nebraskans don’t buy the assurances from TransCanada and the U.S. State Department that the pipeline poses no serious risks to their water, land and livelihoods; farmers and ranchers in other Great Plains states don’t either.

Just look at TransCanada’s Keystone I, a smaller pipeline from Alberta to Illinois that began operation in June 2010. In just over a year, this pipeline has leaked at least 14 times, including a spill of about 21,000 gallons in North Dakota — even though TransCanada predicted that spills of 2,100 gallons or more should be expected to happen only once every seven years.

The tar-sands bitumen that Keystone XL would carry is thick, corrosive, unstable, and hard to clean up. Plains Justice, a nonprofit organization, has documented how ill-equipped the sparsely populated northern Plains states are to respond to an oil spill. The Keystone XL could even be a terrorist target.

Too risky? Absolutely — and that’s even before you get into the grave threat that tar sands oil poses to our global climate.