These bumper stickers have proliferated on cars of those opposed to LNG terminals on Passamaquoddy Bay in Maine.Photo: Erik HoffnerA dramatic environmental justice and cultural survival campaign led by a band of Passamaquoddy tribal elders and members in northern Maine ended in 2010 in favor of indigenous activists. A massive liquefied natural gas (LNG) import terminal, proposed for this coastal reservation by an Oklahoma energy company encouraged by the Cheney Energy Task Force’s bullish policy pushing this fuel, was defeated, but only after a five year battle revealed the inadvisability of Quoddy Bay LNG on economic, technical, and legal grounds.

These bumper stickers have proliferated on cars of those opposed to LNG terminals on Passamaquoddy Bay in Maine.Photo: Erik HoffnerA dramatic environmental justice and cultural survival campaign led by a band of Passamaquoddy tribal elders and members in northern Maine ended in 2010 in favor of indigenous activists. A massive liquefied natural gas (LNG) import terminal, proposed for this coastal reservation by an Oklahoma energy company encouraged by the Cheney Energy Task Force’s bullish policy pushing this fuel, was defeated, but only after a five year battle revealed the inadvisability of Quoddy Bay LNG on economic, technical, and legal grounds.

Citizens groups in nearby Eastport, Maine and St. Andrews, just across Passamaquoddy Bay in New Brunswick, Canada, rallied regional support for the activists by pointing out how the enormous, fuel-laden LNG tankers would pose a safety risk to nearby communities, disrupt commercial fishing operations, and harm tourism (including whale watching and recreation operations).

That’s the happy backstory. Even though LNG is likely preferable to fracked domestic gas due to its more benign derivation as a byproduct of oil drilling, much of the native community’s remaining ancestral land and lifeways would have been industrialized for the benefit of some jobs and lease payments.

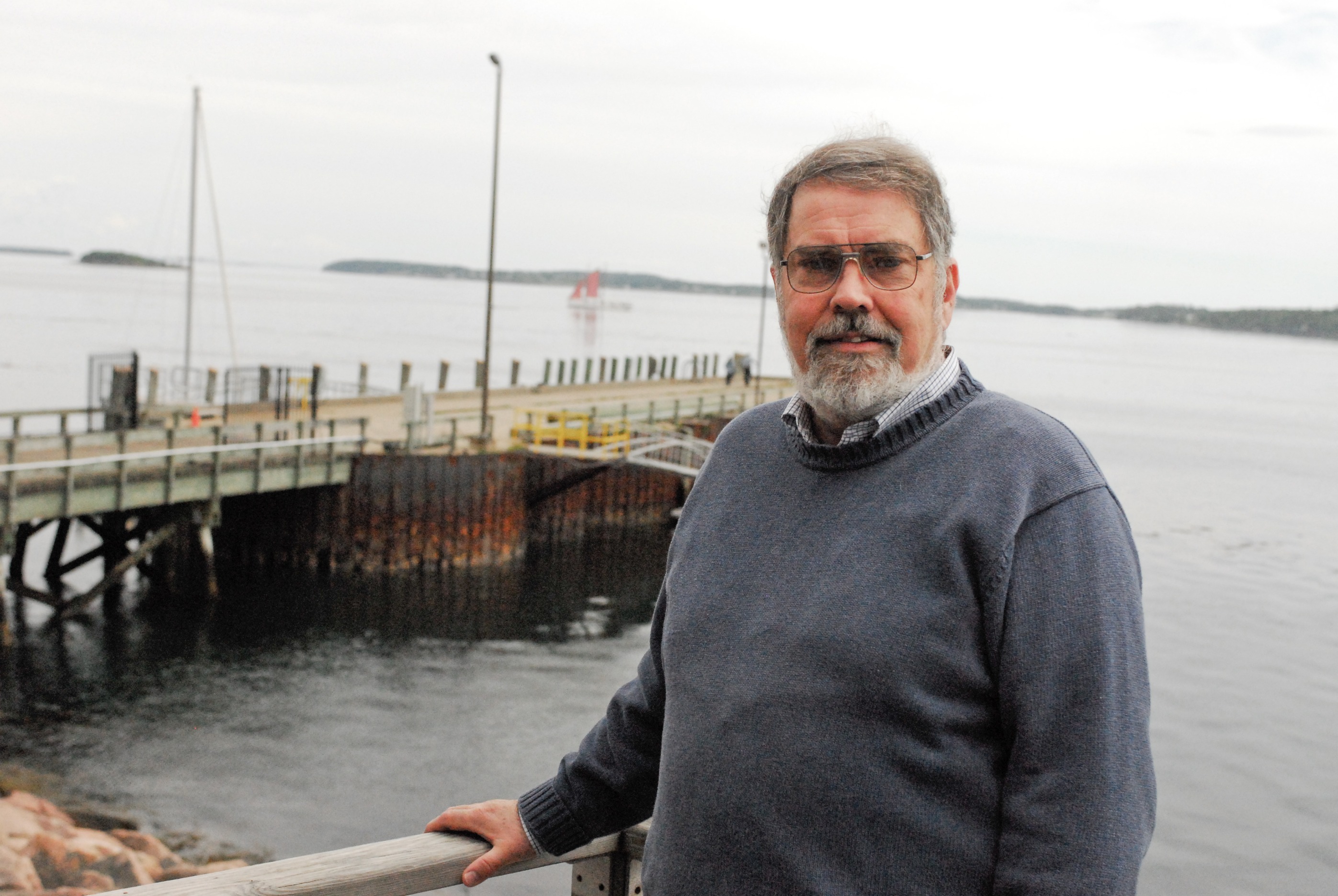

Rob Wyatt, Environment and Permits director for Downeast LNG at the site of the project’s proposed terminal on Passamaquoddy Bay.Photo: Erik HoffnerBut it’s not the end of the story, as another energy company still seeks to site a terminal on the Maine side of the international marine border, farther up the bay from the reservation. The bay’s border status, and the fact that it is an arm of the Bay of Fundy, are among the biggest hurdles faced by Downeast LNG. Passamaquoddy Bay would seem to be a questionable body of water to which to send a 1000-foot ship carrying an average of 888,000 cubic feet of fuel that’s more flammable than oil. Narrow and clotted with islands, it also features tides of 20 feet, which cause the largest whirlpool in the Western Hemisphere to appear twice daily.

Rob Wyatt, Environment and Permits director for Downeast LNG at the site of the project’s proposed terminal on Passamaquoddy Bay.Photo: Erik HoffnerBut it’s not the end of the story, as another energy company still seeks to site a terminal on the Maine side of the international marine border, farther up the bay from the reservation. The bay’s border status, and the fact that it is an arm of the Bay of Fundy, are among the biggest hurdles faced by Downeast LNG. Passamaquoddy Bay would seem to be a questionable body of water to which to send a 1000-foot ship carrying an average of 888,000 cubic feet of fuel that’s more flammable than oil. Narrow and clotted with islands, it also features tides of 20 feet, which cause the largest whirlpool in the Western Hemisphere to appear twice daily.

Besides the strong Fundy currents and dramatic tides, the international border itself presents a much larger problem for LNG ships in Passamaquoddy Bay: To enter it, tankers must transit Head Harbour Passage, which is recognized as being on the Canadian side. But Canada doesn’t want LNG ships using this particular piece of water, and that has caused a quiet but stern border dispute.

A June 29, 2010 letter from a Consul General of Canada formally notified the Maine Department of Environmental Protection that because of navigational, environmental, and public safety risks, LNG transits are prohibited in their “internal waters,” such as Head Harbour Passage. Further, U.S. law requires LNG tankers to have Coast Guard gunship escorts (they are a terror target, according to lawmakers) and Canada does not want foreign, armed vessels in its territory.

Save Passamaquoddy Bay’s Bob Godfrey stands on the Eastport, Maine waterfront at Head Harbour Passage.Photo: Erik HoffnerNew Brunswick Premier Shawn Graham in 2010 reinforced his government’s opposition to LNG tankers in the Passage, and Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper is also on record against the developments. Further, American LNG companies don’t have a legal leg to stand on since the U.S. never ratified the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, according to Bob Godfrey, of Eastport-based Save Passamaquoddy Bay. If the government had, tankers could claim “innocent passage” in the Bay, he says.

Save Passamaquoddy Bay’s Bob Godfrey stands on the Eastport, Maine waterfront at Head Harbour Passage.Photo: Erik HoffnerNew Brunswick Premier Shawn Graham in 2010 reinforced his government’s opposition to LNG tankers in the Passage, and Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper is also on record against the developments. Further, American LNG companies don’t have a legal leg to stand on since the U.S. never ratified the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, according to Bob Godfrey, of Eastport-based Save Passamaquoddy Bay. If the government had, tankers could claim “innocent passage” in the Bay, he says.

Dean Girdis, CEO of Downeast LNG, and his lawyers hotly dispute this. “International law is not on (Canada’s) side and they know it. They’re just protecting their constituents and their own business interests, particularly the Irving LNG terminal in New Brunswick, because we would be a competitor. They will back down, or the U.S. government will take them to court in The Hague and they will lose,” Girdis told me.

Whether or not the court would agree, he could be right about business interests playing a role in Canada’s stance. A new LNG terminal owned by Irving Oil was recently completed 60 miles from the Maine border and sells gas to the same markets in the Canadian Maritimes and New England that Downeast would. That same terminal could begin exporting LNG as well, thanks to extensive shale gas fracking plays recently discovered in the province.

Maine Governor John Baldacci had Downeast LNG’s back on this until leaving office last year, and had written to the U.S. Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) advocating on its behalf (and his Republican successor Paul LePage is just as friendly). Given the recent cross border trade dispute over softwood lumber imports, combined with the high stakes standoff over Canada’s claim to the Northwest Passage, easy resolution to the rights of passage seems unlikely. According to a 2006 report in New Brunswick’s Telegraph-Journal, Harper had promised to “pursue ‘all diplomatic and legal means’ to prevent LNG tankers from transiting Head Harbour Passage. Should Canada do this, one FERC official admitted that the Passamaquoddy (Bay) projects would be dead in the water.”

Better than fracked gas or not, LNG faces hurdles like this everywhere terminals are proposed in the U.S. Lacking consensus on how to handle such developments, local battles and border wars (of words) like this one are sure to continue.