Macomb PaynesConventional farmers add a lot of synthetic nitrogen fertilizer to the soil. Most crops only absorb around 30 to 50 percent of it, leaving many pounds of nitrogen behind. When that soil is tilled, nitrogen can enter the atmosphere as nitrous oxide, a highly potent greenhouse gas, or drain into waterways, before eventually wreaking havoc on our bays and oceans.

Macomb PaynesConventional farmers add a lot of synthetic nitrogen fertilizer to the soil. Most crops only absorb around 30 to 50 percent of it, leaving many pounds of nitrogen behind. When that soil is tilled, nitrogen can enter the atmosphere as nitrous oxide, a highly potent greenhouse gas, or drain into waterways, before eventually wreaking havoc on our bays and oceans.

But that’s not the only downside to tilling farmland. It releases carbon that had been sequestered into the atmosphere, and reduces the amount of water the soil would otherwise retain, putting even greater stress on the world’s emptying water tables. When done regularly, tilling also causes soil to erode. Take all this into account and it’s no surprise that “no-till farming” has gained popularity in recent years.

For most of the 20th century, American farmers tilled under the crop residue (like empty corn stalks) left behind in their fields after harvesting. This practice turns up as much as six inches of soil and is usually done to stop weed growth, though it also loosens the soil to make the next planting easier.

No-till farming, on the other hand, is pretty much exactly what it sounds like. The crop residue is left undisturbed after harvest and the next round of seeds are pushed through it. Since 1989, it has become the dominant form of soil management on conventional operations, covering more than 65 percent of cropland, according to the USDA. No-till has also often been subsidized (at a value of up to $200,000 over five years) in the Conservation Stewardship Program, a grant program that started after the 2002 Farm Bill, and is meant to incentivize farmers to take better care of the water land and air.

Stewart Brand, author of The Whole Earth Catalogue and so-called “father of the modern sustainability movement,” called no-till “the best thing you can do in agriculture for the atmosphere,” in a 2009 interview. “Conventional farmers that are doing this are finding their soil is much richer … just exactly like the organic guys,” he said.

Stewart Brand, author of The Whole Earth Catalogue and so-called “father of the modern sustainability movement,” called no-till “the best thing you can do in agriculture for the atmosphere,” in a 2009 interview. “Conventional farmers that are doing this are finding their soil is much richer … just exactly like the organic guys,” he said.

Sounds good, right? But it’s not quite so simple. The Rodale Institute, a non-profit organic farming research organization, recently confirmed what many critics have been saying for years: No-till, as a stand-alone practice on an otherwise conventional farm, is a no-go.

According to Rodale’s Farm Systems Trial, which has been comparing the results of side-by-side organic and conventional farming systems for 30 years, conventional no-till farming not only uses more inputs, it does nothing to raise the value of the crops produced.

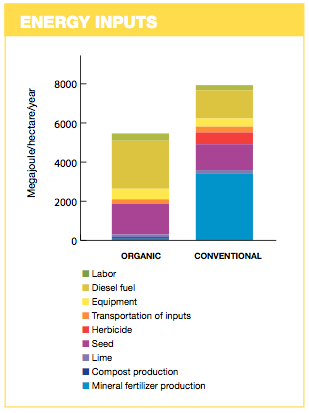

Why is that? Conventional farmers who stop tilling rely heavily on herbicide to kill the weeds the tilling process would have nabbed — or face reduced yields. This herbicide costs money and requires energy to produce (see chart). The study showed that energy efficiency was 28 percent higher in the organic part of the farm than the conventional, where as the conventional no-till system was the “least efficient in terms of energy usage.”

The U.S. Department of Agriculture even warns farmers about the potential pitfalls of poorly practiced no-till farming, saying the cost savings associated with less tractor usage “may be offset by increased crop protection costs and the fertilizers required to attain optimal yields.”

Ken McCauley owns and operates K&M Farms in northeast Kansas. He grows corn and soybeans on a 4,500-acre farm that’s been a no-till, conventional operation since the 1980s. He believes that using no-till methods is better for the earth and describes his farm as “very sustainable.” He takes fewer passes over his fields — therefore using less fuel — and relies on fewer insecticides, since practicing no-till farming reduces the opportunity for insects to breed and is generally known to attract beneficial insects.

Regardless, McCauley still uses approximately 500 pounds each of fuel, Round-Up Ready seeds, and synthetic fertilizer in his operation every year.

Unfortunately, according to the Rodale study, the average net return for organic systems, which rely on no- or low-till practices as an important part of an overall system of pest and soil management, was $558 per acre per year. Conventional no-till corn, which by definition means planting genetically engineered crops and growing them with the assistance of chemicals, brought in just $28 per acre per year (not counting conservation funding, of course).

Meanwhile, there may be ways to harness the value of less tilling within a more holistic farming system. For instance, at Earthbound Farm — the nation’s largest producer of organic salad mix — 37,000 certified organic acres are managed using what Will Daniels, senior vice president of operations and organic integrity, calls a “low-till” system.

How is it done? When an Earthbound field first begins the three-year process it takes to transition a new piece of land to organic, the company plants row crops, such as broccoli, which are relatively easy to weed by hand. After about five years of walking the rows and pulling weeds out by hand, Earthbound farmworkers have not only gotten to know their fields intimately, they’ve reduced the number of weeds that sprout in the first place. Between vegetable crops, they will turn up just half an inch of soil to prepare it for cover-crop planting; this method helps bury remaining weed seeds too deep in the soil to sprout.

When it’s all said and done, tilling is only one piece of the puzzle. As Chris Schreiner, executive director of Oregon Tilth, a nonprofit organic research and certifying organization, put it, “No-till is one system that can improve soil health.” But, “that practice alone does not make the overall system sustainable.”