“Watch out.” That’s what one student leader, Hu Kunzhu, told us in a sweltering university dining hall in Xi’an this August.

We were in this ancient capital of China for the College Environmental Groups Forum, which brought together students from more than 60 universities across the country. These included representatives from the far-flung wealthy provinces of the east coast and the relatively impoverished desert west, together for the first-ever national conference of the country’s quickly emerging — and much needed — student environmental movement.

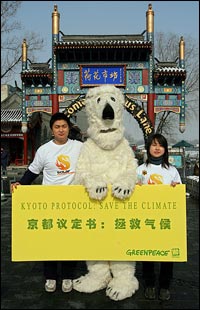

Beijing’s new look.

Photo: © Greenpeace / Natalie Behring

A moment after Hu had issued his warning, he continued with a smile: “Because our goal is to outpace environmentalists in the U.S.”

Coverage of China’s environmental problems by international media has been extensive in recent years. Less widely reported is the valiant work being done quietly across China by as many as 5,000 grassroots environmental organizations that have sprung up over the last decade to clean rivers, plant trees, recycle, and put China on a cleaner path of development. Among these organizations, one can find, as we did, hundreds of university associations and the passionate, energetic students who run them.

You wouldn’t have mistaken the Xi’an conference for one in the United States. For one thing, these students had the kind of attention spans for lectures that American young people lost long ago. For another, instead of spoken word or acoustic guitars, the open mic night featured performances of traditional Chinese epics. During the daytime, we heard from students across the country involved in a variety of projects.

At Nanjing University, a regional organization named Green Stone is protecting a highly endangered species of butterfly by patrolling its mountain habitat looking for poachers, and endeavoring to clean the mighty Yangtze by surveying sources of water pollution on a local stretch of the river. At the Harbin Institute of Technology in northern China, the Green Union plants trees, celebrates World Environment Day, and organizes trips to ecologically sensitive areas during school holidays. A group of student leaders in Beijing is working with Greenpeace China to start campus campaigns for clean energy and has traveled to China’s coal country to document mining’s human and environmental toll.

There was no shortage of such groups; one could also find the Green Volunteers, call out for Green SOS, or spot a Green Angel. Over the past 10 years, recognizing the severity of its environmental crises and tacitly acknowledging that it doesn’t have the ability to rein in corrupt local officials who ignore environmental violations, the Chinese government has allowed environmental organizations to form. Many of the student groups originated with graduates of Green Camp, a hub of the movement that has spent the last decade taking young people on field excursions to threatened ecosystems. During recent years, regional student environmental organizations have been started in almost all of China’s provinces, although they have been stymied at further cross-provincial organizing by a government still wary of a growing civil society.

Up to this point, associations at large schools have tended to focus on simply raising public awareness of environmental issues, planting trees, and recycling. At specialized schools that have an inclination toward the environmental sciences, such as forestry or geoscience universities, students carry out environmental research in their own fields. But following the lead of students operating in the relatively freer political climate of Hong Kong, student groups are now looking at more sophisticated projects that include the kind of campaigns for clean energy increasingly common at U.S. universities.

These activists are starting from scratch, in a society with little or no popular understanding of citizen involvement in public affairs, with large barriers to citizen involvement, and with unknown dangers of running afoul of government officials. Their activities are limited by their schools’ regulations. Nonetheless, to ask them about their motivation for environmental work is to see the universal dedication one finds in environmental activists in countries rich and poor alike. They use words like “duty” and “honor” to refer to their role in protecting China’s environment. Doing her best to convey her feelings in English, Pei Yonggang from the China University of Geosciences in Hubei Province told us that “our flame and sense of duty are the causes of our inspiration.”

They and other grassroots organizations are not completely alone. Some U.S. student groups are funneling assistance to these budding Chinese networks. The Beijing-based Green Student Forum helps to connect organizations in different provinces and leads trainings for activists. Also in Beijing, the Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs, led by the prominent former journalist Ma Jun, will soon unveil a powerful online tool using mapping technology to show pollution levels and pollution sites for waterways across all of China. In a place where information is hard to come by, Ma’s goal is to empower grassroots organizations to hold polluters accountable.

The student leaders are farsighted citizens, representing a generation that is ready to take responsibility for its country’s development. Some are framing environmental protection in terms of the “Harmonious Society” policy that President Hu Jintao introduced in 2005. Drawing on traditional ideas to bring modern environmentalism to the Chinese public and putting a new spin on what a sustainable community looks like, Pei also said, “In the near future, we hope that our university can become a ‘Green University’ or ‘Harmonious Campus’… In China, our vision is that everybody attaches himself or herself to environmental protection actively, and all the people make great efforts to build a ‘Harmonious Society’ together.”

China will certainly need it. It’s hard to overstate the environmental challenges the country faces. The simplest, starkest way to put it may be that in some provinces, double-digit GDP growth is cancelled out each year by the cost of natural capital and human health lost to pollution and environmental degradation. But we have hope. There are almost as many university students in China as in the United States, and these students will soon take a leading role in business and government — hopefully after having been inspired, like us, by the environmental advocates on Chinese campuses.