Jarid Manos.

With what environmental organization are you affiliated? What’s your job title?

I am the founder and CEO of Great Plains Restoration Council, based in Fort Worth, Texas;, Wounded Knee, S.D.; and Denver, Colo.

What does your organization do?

Out here in flyover country, our prairies and plains have been so devastated they have been left for dead. Our region was once one of the most profusely abundant, in terms of ecosystem lushness and volume of life, ever to exist on terrestrial earth. Unfortunately, our region’s recent human history has largely been written in bloodshed, suffering, and sorrow.

But out of the ashes, people from all colors, cultures, and communities are now coming together to protect our remaining intact lands and restore and reconnect others. There is too much violence in the world, and the violence people do to the earth mirrors the violence people do to each other. Our inner-city youth and Indian reservation youth share many of the same social challenges, but rarely interact. They understand the similarities between their own social devastation and the ecological devastation of our prairie. By working to heal the earth, they heal themselves, while developing leadership skills and technical expertise needed to survive and thrive in this world and go forward.

Right now, our Great Plains native wildlife still face aerial gunning, spring-loaded cyanide guns, massive prairie dog poisoning campaigns, killing contests, overgrazing, desertification, bulldozing, and more. Grassland bird populations, which need healthy native prairies to nest (and rest during their long to-and-from flights to Central and South America) are crashing. There are no free-roaming buffalo anywhere, including Yellowstone National Park, where the animals are prevented from coming out of the mountains down onto ancestral High Plains terrain. The great prairie dog ecosystem, once 5 billion strong — the coral reef in the sea of grass, and so important to over 160 native animals — has been killed down to less than a scattered 3 percent. Meanwhile, the last vestiges of tallgrass prairie ecosystems are facing the bulldozer or plow.

But GPRC, through its Buffalo Commons movement, has put forth a new ethic of ecological identity and ecological health, where people work to restore the health of themselves, their community, and their natural environment, proudly steeped in returning life to a gasping land.

What are you working on at the moment? Any major projects?

In South Dakota, GPRC operations are run by Oglala Lakota folk who live on Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. They are working to make sure the South Unit of Badlands National Park, which is inside the reservation boundaries and about to be transferred back to the tribe, is managed and protected as tribal wilderness. Currently, it is used for cattle grazing, and there is also a lot of theft and damage of paleontological, archaeological, cultural, and sacred sites and unmarked graves (from officially undocumented massacres back in the late 1800s). Please contact Badlands National Park and express support for “alternative Z,” which was written with input from Oglala Lakota citizens who live there and approved by traditional tribal elders.

We are also advocating for the upgrading of Buffalo Gap National Grassland, directly north of the reservation, into a Northern Plains unit of a proposed, first-ever Great Plains National Park. Right now, it is the site of the most successful endangered black-footed ferret reintroduction, and the U.S. Forest Service, which “manages” this national grassland for cattle grazing, wants to poison the prairie dog town upon which the black-footed ferret absolutely depends. According to the Native American Times, “The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and partners have spent millions of U.S. taxpayers’ dollars in recovery efforts for the black-footed ferrets. Grazing records indicate that the public lands in Conata Basin feed the equivalent of 700 head of cattle per year — even in non-drought years. At an estimated profit margin of $27 per head of livestock, millions of dollars spent on black-footed ferret recovery would be sacrificed for $19,000 of private profit per year. … The public has [until July 23] to comment on the poisoning plan before the Forest Service issues its final Environmental Impact Statement.”

Home on the range.

In Colorado, we are beginning work on the 55,000-acre Soapstone project, north of Fort Collins, where on this new open space that connects the mountains to the plains we are seeking to have bison restored. There is a 12,000-year-old human history on the land with the buffalo, and we need to continue that into the modern era while providing open space, a true wilderness experience, and multicultural youth education and leadership development programs for Colorado (and other) residents.

In Texas, we are in a pitched battle to save the 2,000-acre Fort Worth Prairie Park area, which is slated for bulldozing, and contains perhaps the richest diversity left in the endangered Fort Worth Prairie ecosystem. I have been all over the Great Plains and have never seen such a lush, beautiful prairie; its nearly 2,400 tallgrass native plant species mirror the richness of tropical rainforests. Our Black community has proudly taken an especially strong lead here and needs to be commended.

Out in West Texas, we also have a new 12,000-acre restoration project coming into the pipeline that needs a lot of work, but which we are very excited about. We plan to leverage this into providing good jobs for both local people, whose economy and population are declining dramatically, as well as ex-offenders statewide trying to stay out of the prison system, through a new “Restoration Not Incarceration” program.

Lastly, our Plains Youth Inter-ACTION program operates in all three states, bringing inner-city youth together with Indian youth to assess and address environmental and health issues and become new leaders in their own lives and for tomorrow’s society. We make sure to always allow youth from HIV/AIDS-affected families access into our youth program’s limited slots.

One last thing: healthy, biodiverse native grasslands function very well as carbon sinks, and research is showing that if the native grasses are kept alive and the roots in the ground, they can hold carbon for up to 8,000 years.

What long and winding road led you to your current position?

In one way or another, the world has always seemed a war zone, full of hatred, ugliness, violence, defeat, and devastation. I reacted in turn, until I saw that my own backlash anger and hate made me little different from the Hate People. I am repulsed by the ongoing violence against the earth, animals, and disadvantaged people. Out here on the Great Plains, my experiences of the violence and danger in the outback made my inner-city hood life look safe. So my life’s work is about creating safe places: for wildlife, for young people, and for anybody who is tired of all the hatred and ugliness and wants our civilization to grow up, live in balance, and build a truly healthy, sustainable future.

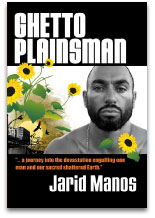

My book Ghetto Plainsman, coming out very soon, tells it all.

What has been the worst moment in your professional life to date?

Spirit is the ultimate wilderness — so the worst moments were where even my spirit was tested to the breaking point. But don’t worry; nothing is going to stop me now.

What’s been the best?

The incredible blooming of our youth leaders.

What environmental offense has infuriated you the most?

Prairie dog killing contests.

Who is your environmental hero?

Tecumseh, vegan Coretta Scott King, Khalil Gibran, Esteban the Moor, President Gore, Wangari Maathai, all the children in our Plains Youth Inter-ACTION program, and Malaya, the prairie dog who was blinded in a poison gas attack, was rescued, and lived on for years to bring fierce inspiration to many people.

What’s your environmental vice?

Sometimes I take too-long showers.

How do you spend your free time (if you have any)? Read any good books lately?

Free time?! I look forward to reading Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man once my book finally is done in the next few weeks.

What’s your favorite meal?

I’m on the board of directors for the Black Vegetarian Society of Texas, where I met renowned artist (and GPRC board member) Evita Tezeno. She cooks all the time for me now. Her vegan meal of barbecued tofu, spicy collard greens, and vegan mac-n-cheez or jalapeno-blueberry cornbread will knock you off your chair (and keeps this vegan athlete healthy and strong enough to fight another day).

Which stereotype about environmentalists most fits you?

Ha ha ha. None.

What’s your favorite place or ecosystem?

The Fort Worth prairie — our nation’s “prairie rainforest”!

Who was your favorite musical artist when you were 18? How about now?

When I was 18, none. Now, Nas.

What’s your favorite TV show? Movie?

I don’t watch or own a TV. The world is my TV. My favorite movie would be Beloved, or The Big Blue.

If you could have every InterActivist reader do one thing, what would it be?

Become a GPRC member; support the rebirth of America’s heartbroken Great Plains.