Mary Anne Hitt.

What’s your job title?

I’m the executive director of Appalachian Voices.

What does your organization do?

We bring people together to solve the big environmental problems facing the central and southern Appalachian Mountains — mountaintop-removal coal mining, air pollution, and the loss of our native forests.

What are you working on at the moment?

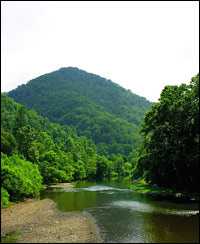

Photo: iLoveMountains.org

We recently launched iLoveMountains.org, an online organizing campaign. Our goal is to build a national network of people who will work together to pass legislation that will end mountaintop removal, a form of coal mining that involves blowing up entire mountains and dumping the rock into valleys, burying streams. It’s devastating the land and communities in West Virginia, Kentucky, Virginia, and my home state of Tennessee.

The centerpiece of iLoveMountains is the National Memorial for the Mountains, which uses Google Earth to show the locations and tell the stories of the over 470 mountains that have been destroyed. With a click of a mouse, all 200 million people who have Google Earth can now see memorials of featured mountains, a mine site tour, and high-resolution images before and after the mining. Last week, Google included the Memorial as part of the newest featured content in Google Earth, and thousands of new people have already signed on to support the campaign.

How do you get to work?

I live three hours away from the main Appalachian Voices office in Boone, N.C., so I mainly work at home, which is a real luxury. But I do drive down to Boone at least twice a month to spend time with the rest of our staff.

What long and winding road led you to your current position?

I grew up in Gatlinburg, Tenn., which is the main tourist gateway to the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, and the home of Dollywood. The development there goes right up to the boundary of the national park, and throughout my life, I watched the go-kart tracks, outlet malls, and housing developments take over one farm after another. It was enough to turn anyone into an environmentalist — at least, that’s what it did for me.

At the University of Tennessee, I founded Students Promoting Environmental Action in Knoxville (SPEAK) and helped write a blueprint for greening the university. Some 10 years later, UT Knoxville has a campus environmental policy as well as a green energy fee that the students imposed on themselves by ballot referendum, making the campus one of the largest buyers of green power in the South. Considering that there wasn’t a student environmental group or any environmental majors on campus when I arrived, I carry my experience at UT with me as proof of the power of a group of dedicated people to shift even the largest, most entrenched institutions.

I’ve been the executive director of three grassroots environmental groups since then, the Southern Appalachian Biodiversity Project in Asheville, N.C.; the Ecology Center (now part of the WildWest Institute) in Missoula, Mont.; and now Appalachian Voices.

Where were you born? Where do you live now?

I was born in Philadelphia but only lived there for four months. I was raised in east Tennessee, and now I live in Blacksburg, Va.

What has been the worst moment in your professional life to date?

One of the most challenging moments of my career was the fight over salvage logging in the Bitterroot National Forest in western Montana after the fires of 2000. I was the executive director of the Ecology Center at the time, and we were one of the dozen or so groups who had filed lawsuits over various components of the plan. The judge sent all the groups into court-ordered negotiations, and we reached a compromise that spared most of the roadless lands and bull-trout habitat, but also allowed a great deal of logging. The settlement was controversial, and the experience taught me a great deal about the difficult choices and harsh realities of serious environmental work.

What’s been the best?

Last year, Ed Wiley, a grandfather and former coal miner from West Virginia, walked from Charleston, W.Va., to Washington, D.C., to raise awareness about the plight of Marsh Fork Elementary School, which is located next to a coal processing facility that releases coal dust onto the school and below a leaking earthen dam holding back 2.8 billion gallons of coal sludge. Ed was promoting the Pennies of Promise campaign to build a new school in a safe location.

Ed’s arrival in D.C. coincided with a Mountaintop Removal Week in Washington that Appalachian Voices organized, which brought volunteers from 13 states to meet with members of Congress. I’ll never forget seeing Ed taking the last steps of his 450-mile pilgrimage. Hundreds of supporters walked the final blocks up Constitution Avenue. That moment stands out in my mind as one of the most powerful of my entire life.

The fate of the school still hangs in the balance. We’re having another Mountaintop Removal Week in Washington May 12-16, and we would love for Grist readers to join us!

What environmental offense has infuriated you the most?

Photo: iLoveMountains.org

For those of us who see the impacts of mountaintop removal firsthand — massive explosions, toxic runoff, lakes of sludge behind earthen dams, families who have lost their homes and lives, and the obliteration of some of the oldest mountains on earth — the increasingly widespread use of the term “clean coal,” even by some environmental organizations, is a bitter pill to swallow. The people of Appalachia know all too well that coal is not delivered immaculately to the power plants, and there is nothing in the so-called “clean coal” technologies that addresses the impacts of mining.

Who is your environmental hero?

My mom and dad have been my biggest inspirations. My dad was the chief scientist of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park for 10 years, during the height of the air pollution and acid rain problems in the 1980s and 1990s. My mom has been a schoolteacher and is now a school principal, and I learned from her that when it comes to changing the world, there’s no shortcut for reaching one person at a time.

What’s your environmental vice?

My car, definitely. Isn’t that how everyone answers this question?

How do you spend your free time (if you have any)? Read any good books lately?

My absolute favorite thing in the world is backcountry canoe camping with my husband, my dog Huck, and some frosty beers in the cooler. I also play a little guitar and love to sing, mostly bluegrass and Americana.

I recently re-read William Faulkner’s Light in August, one of my favorites. I’m a sucker for that Southern gothic style. I think the new book Big Coal by Jeff Goodell should be required reading for every environmentalist.

What’s your favorite meal?

It’s 100 percent from my summer garden — fresh sweet corn, green beans, and a salad with homegrown tomatoes, basil, and fresh mozzarella. For dessert, black raspberry cobbler from the raspberry patch that’s taking over the pasture behind our house.

What’s your favorite place or ecosystem?

The Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The Appalachian Mountains are one of the most diverse ecosystems on earth — second only to the tropical rainforest — and new species are being discovered there all the time.

If you could institute by fiat one environmental reform, what would it be?

I would take the billions of dollars of subsidies the federal government is currently handing out to fossil-fuel industries and invest them in clean, renewable energy and energy efficiency instead. America is an innovative, optimistic nation, and I firmly believe that if we shifted the focus of our resources and ingenuity to transforming our energy systems, we could produce the energy we need without destroying the climate, the land, communities, and human lives.

Who was your favorite musical artist when you were 18? How about now?

Then, R.E.M.. Now, alternative country is my mainstay, and I’ve also been hooked on Coldplay lately.

What’s your favorite TV show? Movie?

TV: The Daily Show and The Colbert Report.

Movie: Harold and Maude.

Which actor would play you in the story of your life?

What 30-something woman and activist would not want to be played by Angelina Jolie?

If you could have every InterActivist reader do one thing, what would it be?

Sign up to join the national network of people working together to end mountaintop removal. Watch this video featuring Woody Harrelson and Willie Nelson, and help us spread the word. We need your help.

What is Appalachian Voices doing to promote renewable energy and conservation to get the U.S. off its fossil-fuel addiction? — Kristen Sykes, Asbury, N.J.

Mary Anne Hitt, Appalachian Voices.

While stopping mountaintop-removal coal mining does not require transitioning away from the use of coal, a sensible plan for America’s energy security and stability does. Not only is coal the biggest contributor to global-warming pollution, but the U.S. Energy Information Administration predicts America will become a net importer of coal in the next five to 10 years. My own state of Virginia is already importing a significant proportion of our coal from Indonesia and Venezuela.

Appalachian Voices is working with allies, including Coal River Mountain Watch, to promote wind power as an alternative to coal mining in the “coalfields” of West Virginia. We recently completed a study showing that the wind resources on Coal River Mountain in Raleigh County, W.Va., if fully developed, could produce in less than 100 years as much energy as the 6,000-acre mountaintop-removal site that mining companies are proposing for that mountain. A slideshow about that study is available on the Appalachian Voices website.

We hope to do a lot more to promote conservation, efficiency, and renewable-energy technologies in the future, but in all honesty, with 14 new coal-fired power plants proposed for our region, we’re playing a lot of defense these days. To learn more about how you and everyone you know can do your part to reduce use of fossil fuels, I recommend the great movie Kilowatt Ours — check it out and host a viewing for your friends.

What do you think of environmental groups who trumpet gasified coal with carbon sequestration as solving the environmental problems associated with coal? — Roger Smith, West Hartford, Conn.

They’re putting a lot more faith in the promises of the coal industry than anyone from Appalachia ever would. Most of the so-called “clean coal” technologies being promoted are much more expensive than current coal-burning plants, have not been tested on a large scale, and will not be viable for decades into the future. Our fear is that this is a classic bait-and-switch — the industry will make promises about implementing these technologies in the future, but will in fact build another generation of traditional coal-fired power plants, creating an even bigger global-warming problem.

I don’t necessarily think groups promoting these technologies are saying that they solve all of the problems associated with coal, but I do think such groups are misguided in their willingness to reinforce the energy industry’s “clean coal” message. The idea that carbon sequestration and other considerably less impressive technologies they call “clean coal” will solve all the problems associated with coal is precisely the idea the energy industry is promoting to support their push for 150 new coal-fired power plants across the country.

These technologies don’t address the impacts of mining in any way, and when groups promote these technologies without putting substantive resources into fighting the impacts of mining, Appalachia’s land and people pay the price. It is Appalachian Voices’ position that coal that comes from mountaintop removal — destroying homes, communities, mountains, and an entire culture — can never be considered clean.

Isn’t there some common ground (no pun intended), in which the coal industry could restore the land they strip, similar to the old logging principle of reforesting after harvest? — Rives Stoll, Lexington, Ky.

In principle, the coal companies are only supposed to be removing mountaintops if they have a plan to develop the site for a commercial use. In reality, less than 1 percent of the sites have had any sort of development on them. The mining companies often go bankrupt before the reclamation begins, and the bond they post for reclamation is usually inadequate. Most former mountaintop-removal sites look like anemic golf courses and will never again support the diverse hardwood forests that once covered the mountains.

Former mountaintop-removal sites are also often damaged to the point of being economically useless, due to unstable geology, massive cracks and destruction of groundwater aquifers by blasting, and severe water pollution. A prison that was built on a former mountaintop-removal site in Kentucky is now called “Sink Sink” because the ground beneath it has continued to shift, and repair costs are so high it’s on track to become the most expensive federal prison in U.S. history.

We’re very supportive of quality restoration — it could easily supply a few hundred years of good jobs in the region. But restoration and development should not be used to justify another acre of mountaintop removal. There are already hundreds of thousands of acres of existing mountaintop-removal sites available for that.

Some see coal liquefaction as an answer to U.S. dependence on foreign oil. With peak oil quite possibly upon us, the price of oil climbing, and evidence that ethanol is a partial solution at best, the pressure to build these plants in coal country will be enormous. Do you think there is any hope of fending off coal liquefaction plants? If not, what will be the impacts? — Mary Wildfire, Spencer, W.Va.

Coal liquefaction is one of the biggest looming threats to both the mountains and the climate. For those who haven’t heard of it, the idea is to turn coal into a liquid that can be used for transportation fuel in jets and cars. Clearly, the increased demand for coal would be catastrophic for Appalachia and other coal-producing regions of the country. Liquefying coal also creates twice as much global-warming pollution as gasoline — a hybrid car run on liquid coal would pollute more than a gasoline Hummer!

Unfortunately, there are some heavy hitters from coal states in Congress lining up behind liquefied coal, including Senator Barack Obama and Virginia Rep. Rick Boucher. I do believe there is hope of fending off these plants, especially as the real-world costs of global warming and mountaintop removal continue to mount. A significant outcry from the public will be critical to stopping this ill-advised liquefied-coal rush, so please contact your members of Congress today.

How do you stay fresh and energized in your job when every day you have to confront the loss of the place you love? — Baird Straughan, Takoma Park, Md.

In a nutshell, it’s the people and the mountains I love that sustain me. I’m surrounded every day by wonderful, supportive, funny people who make my life a real joy — my husband, family, friends, and colleagues at Appalachian Voices and beyond. Without them, I might have thrown in the towel a long time ago.

Whenever I’m starting to feel worn down and overwhelmed, the best remedy is to put on my running shoes and head out to the national forest behind my house for a run on the trails with my dog Huck (have I mentioned that he’s the best dog ever?). It’s amazing how much my outlook on life improves after a little exercise and fresh air. Meditation has also been very grounding for me.

One of the great ironies of doing professional environmental work is that it actually becomes harder for many of us to find time to enjoy the outdoors. But in my experience, when we think we just can’t spare any time for ourselves or pull ourselves away from the computer, we’re often less effective (not to mention less pleasant to work with) in the long run. For those looking for tools to find that balance, as well as other great professional-development opportunities, I would encourage you to check out the Environmental Leadership Program (I am a current fellow) and Baird’s organization, the Institute for Conservation Leadership.

What can college students with limited budgets and resources do to help in battling the environmental issues in Appalachia? — Whitney Jones, Lexington, Va.

Organize on your campus to demand that your university stop purchasing electricity generated by mountaintop-removal coal. At my alma mater, the University of Tennessee, the faculty Senate, grad student Senate, and Student Government Association have all recently passed resolutions urging the administration to adopt a policy of not buying surface-mined coal.

You can also help reduce the demand for mountaintop-removal coal by increasing the use of renewable energy on your campus — several universities in the South have done this by creating a new student fee to purchase large blocks of green power. Universities use a tremendous amount of electricity, so they offer a great opportunity to begin to shift energy use in this country.

Students across the South are working on these campaigns on their campuses, and you can connect with them through the Southern Energy Network. The Mountain Justice Summer campaign provides opportunities for students who want to spend their summer getting their hands dirty working with groups in Appalachia. The Energy Action Coalition is a national student network and a great resource.

You mentioned discomfort with allowing salvage logging in Montana when you were at the Ecology Center. Do we really gain anything by compromising? Isn’t it really too late to compromise on the commercial development and extraction of resources on public lands? As a movement, where do you think we would be today if our actions had been consistent with our deeply held principles? — Sam Hitt, Santa Fe, N.M.

The issue of compromise is always the $64,000 question in any environmental fight. When the national surface-mining law was passed in 1977, a compromise was made to allow mountaintop removal, a loophole big enough to drive a few million coal trucks through. The modern-day movement to end mountaintop removal learned a very important lesson from that experience, and we are keeping those lessons in mind as we work to pass new federal legislation to curtail mountaintop removal, the Clean Water Protection Act.

On the other hand, wilderness advocates today often make concessions for less protective designations that provide all the protections of wilderness but allow for mountain bikes, which are prohibited in wilderness areas, in order to get the support of mountain bikers for wilderness bills. Would it have been better if these concessions were not made and these new wilderness areas were not added to the system? I think that’s a more difficult call.

My lesson from the Bitterroot was as much about learning to negotiate — being willing to give some things up while also being very clear about your bottom line — as it was about the perils of compromise. Too often, I think environmentalists set the bar too low initially, giving themselves no room to maneuver without undermining their core principles. Here in the East, protecting our public lands, which harbor some of the last vestiges of our once majestic forests, is definitely a core principle for millions of us.

I’m from Sevier County, Tenn., too, and I became invigorated to spread the word about mountaintop removal from the realization that our precious Smoky Mountains are protected by the National Park Service’s rubric of preservation, but the wonderful mountains in West Virginia enjoy no protections. When I become complacent, I imagine a dragline taking Mount LeConte away — I always have a physically nauseating reaction to that thought. What stirs your passions and keeps you fighting? — Joshua Hill, New Haven, Conn.

Wow, you’re from Sevier County too? For the rest of our readers, this doesn’t happen every day. The image of a dragline taking away Mount LeConte — the most famous peak in the Smokies — resonates a great deal with what drives me. The mountains I can see from my parents’ front porch are the closest to my heart, and when I think of them being blown up and hauled away, it is almost more than I can stand.

This very nightmarish scenario is not just a dream — it’s actually happening, as we speak, to people throughout West Virginia, Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee. My friend Maria Gunnoe, who lives in Bob White, W.Va., and is a community organizer with the Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition, lives on property that has been in her family for generations. She is now being forced to watch as the mountains that she sees from her front porch are systematically dismantled and destroyed. The daily blasting covers her and her family with toxic fumes from blasting agents and dust that covers everything, including the inside of her freezer. Her family is often sick from respiratory problems and their once-peaceful lives have been ruined.

I would like to think that if coal companies were destroying the mountains I see from my parents’ front porch that I would not be alone, that people would come and help me try to save them. So that is what I am doing, along with you and thousands of other people from across Appalachia and the nation. Thank you for being one of those voices for the mountains and spreading the word!

I seem to remember you received some notoriety in Mother Jones for an action SPEAK did to help the Tennessee Valley Authority pay for its $25 billion debt. The details of the action escape me, but it was all the buzz around TVA for several months. What did you and SPEAK do to get so famous? — Steve Hixson, Westford, Mass.

When I was a student at the University of Tennessee, the Tennessee Valley Authority was attempting to start up the last nuclear power plant to go online in the nation, the Watts Bar facility in east Tennessee. It was notorious for safety problems, whistleblower complaints, and massive cost overruns that had contributed heavily to TVA’s $25 billion debt.

As the young people who would be saddled with this debt in the future, the members of SPEAK decided to help pay off the debt by holding a bake sale in front of the TVA headquarters in Knoxville. While we didn’t raise quite enough money to pay the debt, we did raise a good deal of awareness. Due to SPEAK and our campaigns around TVA and Watts Bar, in 1996 the University of Tennessee was recognized as one of the top 20 activist universities in the nation by Mother Jones magazine.

How is your work shaped by the fact that you are a woman? Is it an advantage, perhaps in seeing the problem? Is it a disadvantage, perhaps in getting heard? It seems to me that it’s usually women who do the kind of work you do — thinking globally, acting locally. — Vera Whisman, Ithaca, N.Y.

I wrote my master’s thesis about five women who played a prominent role in the history of the wilderness movement, and one of the things I learned was that it’s a challenge to generalize the experience of women who do environmental work. With that said, I do think that most women I know tend to prefer a collaborative work style, instead of the lone-wolf approach, which is beneficial in advancing efforts that include many partners. I also think many women find it natural to maintain extensive webs of relationships, which serves me well in keeping up with the dozens of people that make our work possible, including our staff and board, volunteers, the staff of partner organizations, funders, the general public, and so on.

Women also face some unique challenges. Most environmental organizations are dominated by very confident and opinionated men, and some women are not comfortable asserting themselves in those circles. Trying to balance motherhood and work in a society that does not provide support like maternity leave or child care is a daunting challenge in any field, and is even more difficult in nonprofit environmental organizations with traditionally low salaries, limited benefits, and long hours.

You give your (speaking) voice to the struggle against mountaintop removal, but you’ve got quite a singing voice too! Any chance you could provide a download of a song? — Matthew Koehler, Missoula, Mont.

|

|

How sweet of you — thank you! The song “The Most Beautiful Place in the World” was included on a benefit CD called Moving Mountains. I encourage Grist readers to purchase a copy, as all the proceeds benefit communities affected by mountaintop removal. You can play the song from the box above, or download it here.