We’re starting to see pieces of counterfactual history on the climate bill in The New Republic and elsewhere based in part on a widely debunked “false narrative.” Since cap-and-trade has been so vilified by the entire right wing and even some on the left, I thought I would try to set the record straight on some key points.

I’m not here to say cap-and-trade was the “correct” strategy. And it may be that any strategy was extrinsically “doomed to fail” — that the Senate’s anti-democratic, super-majority 60-vote “requirement” meant that a dedicated minority could have killed any approach — once the Republican Party decided to become the only major political party in the world dedicated to denying science and blocking any action.

I mainly want to show that cap-and-trade was not intrinsically doomed to fail, that it was not obviously or inherently a flawed idea in, say, 2008 — or even 2009. Quite the reverse. Only someone who doesn’t know history — or who chooses to ignore it — could believe that.

Environmentalists and progressives and others pursued cap-and-trade for several reasons, most of which have been utterly ignored by the counterfactual revisionists:

- The obvious alternatives — especially a tax and a major push on clean energy — had been harshly rejected, primarily by Republicans. They were both widely seen as divisive and failed strategies. The BTU tax was killed in the Senate, primarily by the GOP, in 1993 and widely seen as contributing to the loss of control of the House by the Democrats. Clean energy — both research and development as well as deployment programs — have been rejected by Republicans for decades, starting with Reagan gutting Carter’s clean energy push. Reagan cut renewables R&D deeply, along with efficiency, clean energy deployment, tax credits — he even took solar panels off the White House. In spite of that, Clinton and Gore tried to meet our Rio Treaty greenhouse voluntary commitment [yes, an oxymoron], returning to 1990 levels by 2000 — with an “innovation agenda,” but Gingrich and his fellow GOPers campaigned against the Department of Energy and its clean energy programs and gutted many of them once in power.

- Cap-and-trade had strong bipartisan political support, with genuine Senate GOP champions. Indeed, it was essentially a Republican market-based idea embraced by Reagan and both Bushes. A cap-and-trade bill for clean air pushed by Bush Sr. had passed Congress easily: “The House of Representatives (401-21) and the Senate (89-11).” George W. Bush had actually campaigned in 2000 on a cap-and-trade for utility CO2 emissions. People who hated clean energy, like McCain, were ardent supporters of cap-and-trade. Heck, even clean-energy-destroyer Newt Gingrich endorsed it! Even after McCain abandoned it, Lindsay Graham embraced it. But once a cap-and-trade bill became a real possibility after Obama was elected with large Democratic majorities, the fossil fuel industry and conservative movement launched a voracious effort to undo this bipartisanship — especially after the House passed a cap-and-trade bill with some moderate Republican support. Perhaps everyone was duped by this bait-and-switch, but there is little doubt they would have launched a similar effort against any plausible strategy.

- Cap-and-trade had strong public support. It retained support in 2009 even though opponents of the climate bill vilified it with a brilliant disinformation campaign and even though opponents of climate bill far outspent environmentalists. People still confuse polling on global warming and climate science with polling on whether/how the government should go about addressing global warming.

- Cap-and-trade had strong business support, especially from the crucial electric utility industry. Could you pass a climate bill that the utility industry opposed? Now that seems like a strategy intrinsically doomed to fail. But in this case the utility industry had experience with cap-and-trade and had been brought to the table through the U.S. Climate Action Partnership. Many other major companies were also on board with this strategy. Yes, it meant that utilities were going to demand a substantial fraction of the allowances, much as they had gotten 97 percent in the sulfur trading program of the bipartisan Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990. I am aware that many of my fellow progressives think that we should have had a cap-and-dividend program where the money goes back to the public — but the big problem with this bill was not public support. We had that. Yes, it might have been broader than it was deep, but absent the support of utilities, no bill could have passed the House.

- Cap-and-trade could plausibly achieve the key goal of reducing greenhouse-gas emissions, whereas an “innovation agenda” couldn’t. I had issues with the final version of the climate bill, but one thing is certain, a purely clean energy agenda could not achieve the primary goal of a climate bill. Indeed, during the mid-1990s, I had overseen the most detailed analysis ever performed on how clean energy (efficiency and renewables and cogeneration — and including natural gas and nuclear power) could cut emissions. It was performed by five national laboratories (See the full study here and some history on it by California Energy Commissioner Art Rosenfeld here [PDF].). That analysis showed that without a price on carbon, clean energy would mostly displace new natural gas, not old coal. Only a price on carbon gets you the emissions reductions. A massive ramp-up in clean energy spending would be great, but it’s always been strongly opposed by conservatives and in any case couldn’t possibly solve the problem. A carbon tax could reduce emissions, but it was a political nonstarter.

- Cap-and-trade could allow the U.S. to make a firm, credible GHG reduction commitment to the world, which was an essential prerequisite for a successful international agreement, which is vital for addressing the problem. The Europeans had already embraced cap-and-trade, so it was viewed as credible internationally, despite the obvious flaws in the market for international offsets (the clean development mechanism). Indeed, internationally it was viewed as a good idea that the United States would join this larger market. We could never have come to the table with just a clean energy spending program. Everyone in the world had already seen in the 1990s that we couldn’t deliver with that.

- Cap-and-trade could pay for domestic and international adaptation efforts — as well as an international regime to stop deforestation. We keep being told that adaptation is important strategy — but it ain’t cheap. Anyone who truly believes we should be spending money on adaptation has to support a bill that generates substantial revenues to do so — otherwise they merely support rhetorical adaptation, whose inevitable result is misery and/or triage and/or abandonment, which have been the main adaptation strategies of choice so far.

- Cap-and-trade could pay for a major clean energy effort. Money doesn’t grow on trees. The folks who somehow claim this could all be done with a massive ramp-up in clean energy funding still need to pay for it in an era of big deficits. If their answer is a carbon tax, as the leading proponent of this approach, the Breakthrough Institute, proposed, then they would have been trying to sell two polarizing, failed ideas at the same time. And that’s all for a strategy that would not allow an international treaty to be signed and wouldn’t actually reduce U.S. greenhouse-gas emissions. That isn’t just a doomed-to-fail approach. It is a suicidal one.

This is not to say that the environmental and progressive movements didn’t make mistakes. I have discussed many of them, including the wrong message and lack of a hard push by the president.

Indeed, cap-and-trade itself clearly has its flaws. It is complex to explain and market-based solutions seemed less appealing in an era when markets were failing — although that last point could not have been anticipated when the strategy was being developed.

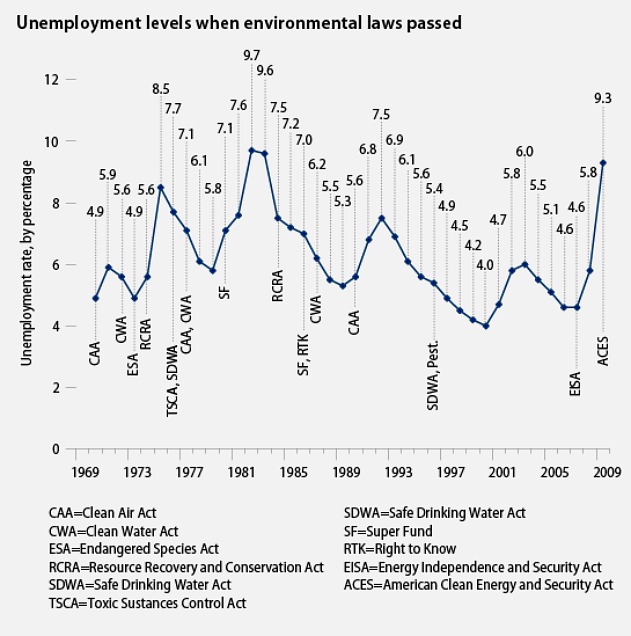

My colleague Dan Weiss likes to point out that we simply don’t pass environmental legislation when the unemployment rate is high, as he explained in his excellent post, “Anatomy of a Senate Climate Bill Death“: “The deep recession, unified and uncompromising opposition in the Senate, and big spending by oil, coal, and other energy interests all had big roles in preventing climate legislation from moving through the Senate this year.” He notes, “an analysis of the unemployment rate when fundamental environmental protection laws were enacted since Earth Day 1970 found that the annual unemployment rate was 6 percent or lower most of the year of enactment”:

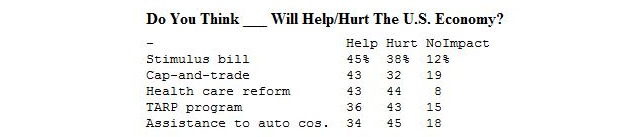

That said, the public did support action — and specifically cap-and-trade — in spite of all the obstacles.

Here’s a table from an Allstate/National Journal Heartland Monitor poll [PDF] of 1,200 Americans conducted Jan. 3 to 7, 2010:

But we needed 60 votes in the Senate, and the conservative movement and the disinformation campaign were able to make that anti-democratic, super-majority “requirement” impervious to public opinion, especially in the absence of a major public push by the president of the United States — and in face of a collapse in media coverage.

The 41 votes needed to kill anything in the Senate can come from states who comprise far below 40 percent of the population. So the media’s failings and the big spending advantage the opponents of the bill had really do matter in the Senate, much more than in the House, where a bill’s overall popularity with the public makes it considerably easier to pass. Counterfactual histories can claim otherwise, but only by ignoring history and by using phony scholarship.

This is not meant to be a definitive analysis of the climate bill and what went wrong. And I do intend to do further posts on this. But the notion that pursuing cap-and-trade was a strategy that was intrinsically doomed to fail is simply wrong. Could it have been done better? Yes. Would doing it better have worked? Who knows? But was there an obviously superior alternative that met even a majority of the eight critical features of a cap-and-trade bill described above, let alone all of them? No.