South Africa’s finance minister, Pravin Gordhan, has an op ed in the Washington Post that illustrates the multi-faceted challenges facing developing nations as they struggle to provide the affordable access to modern energy needed to pull citizens out of poverty. The piece highlights the current tension between such objectives and simultaneous concerns about the environmental and climate impacts of energy development.

With South Africa’s economy growing rapidly — it’s expanded by two-thirds since 1994, when Nelson Mandela first took office — the nation’s demand for energy has grown apace. As Gordhan notes, “Millions of previously marginalized South Africans are now on the grid.” And that’s a very good thing.

Consider that not having access to affordable, modern energy sources, particularly electricity, means no access to potable, running water; it means having to burn dung and wood and other primitive biofuels to provide cooking and indoor heating; and it means sputtering kerosene lamps as the only source of light after the sun goes down.

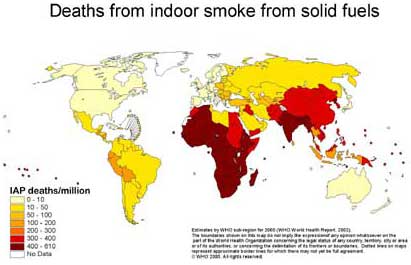

The human toll of such energy poverty is incredible. According to the World Health Organization, solid fuel use causes 1.6 million excess deaths per year globally, especially among women and children, while waterborne disease is one of the leading global killers, ending the lives of over 3 million annually — again, many of them young children — who lack access to clean and safe water supplies.

Image source: WHO

Image source: WHO

Don’t forget, as well, that the constant time requirements of collecting water and fuel keeps most women and children in energy poor nations locked out of the empowerment and opportunity that comes from a basic education and participation in the trade economy.

It is not an exaggeration to say that energy poverty fuels a cycle of poverty and death that can only be broken through access to affordable sources of modern energy — particularly electricity.

But as the economy has grown and access to modern energy has begun to end the cycle of energy poverty for millions of South Africans, there, “as in other major emerging economies, [energy] supply has not kept pace,” Gordhan writes. “To sustain the growth rates we need to create jobs, we have no choice but to build new generating capacity — relying on what, for now, remains our most abundant and affordable energy source: coal.”

And therein lies the dilemma.

Given the challenges of financing major capital projects like power plants in the midst of the Great Recession, South Africa and the national utility, Eskom, have turned to the World Bank, the African Development Bank and the European Investment Bank for assistance in financing new electric power stations. But their $3.75 billion loan request to the World Bank ($3 billion for a major new coal-fired power plant and $750 million for new wind and solar facilities) now “faces stiff opposition,” according to Gordhan. The reason? Concerns about the effect of new coal-fired power plants on the destabilizing climate.

Gordhan explains:

South Africa takes climate change and the need to reduce fossil fuel emissions extremely seriously … If there were any other way to meet our power needs as quickly or as affordably as our present circumstances demand, or on the required scale, we would obviously prefer technologies — wind, solar, hydropower, nuclear — that leave little or no carbon footprint. But we do not have that luxury if we are to meet our obligations both to our own people and to our broader region whose economic prospects are closely tied to our own. South Africa generates more than 60 percent of all electricity produced in sub-Saharan Africa. Tight supplies are not just a problem for us.

The simple fact is, without access to clean and cheap energy sources, developing nations like South Africa will continue to turn to coal. They must, as the challenges of ending energy poverty and pulling millions of their citizens out of poverty demands it.

As I’ve written before, until clean and cheap energy sources are available for deployment on a massive scale, developing nations like South African will remain stuck in the Development Trap: forced to either sacrifice climate and ecological security in the name of development and poverty alleviation or to condemn countless millions of citizens to energy poverty in the name of climate protection.

Breaking out of this untenable position is the urgent challenge of the century. The only way out of the Development Trap, and the only route to sustainable development and an end to pervasive energy poverty is to make clean energy cheap. On that front, the world can’t afford to delay.

Anything else is ultimately counter-productive, ineffective, or even cruelly unjust, a point that Minister Gordhan appears keenly aware of:

A question that has to be faced is whether stunting growth prospects in our region will in any way serve the goal we all share of eliminating greenhouse gas emissions over the long term. Whatever paths we take toward that goal, whether shifting to renewables and nuclear, or finding ways to keep harmful gases out of the atmosphere once created, the journey will inevitably be costly, requiring massive investments in technology, research, and re-engineering the ways in which we live and do business. It will also require a true spirit of consensus and collaboration.

Neither of these requirements will be well served by hampering the transitional measures that developing countries like ours need to take to get themselves on sustainable growth tracks and generate the resources they need to play their part in preserving our planet.

We must make clean energy cheap. There is no time to waste.