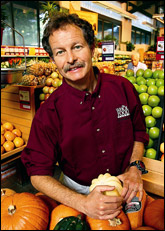

John Mackey wants you to buy his organic squash.

He’s the Bill Gates of organic foods. John Mackey, founder and CEO of the Whole Foods empire, started his original health-food store, called Safer Way, in a garage in Austin, Texas, in 1978. Local farmers would drop off produce from junky old pickups, hippie bakers would supply nut loaves and 20-grain bran muffins. It was strictly vegetarian, just like Mackey himself.

But he soon realized he’d have to change his tune if he wanted to hit the big time, and change it he did. Whole Foods now offers everything from beer and rack of lamb to yoga mats and air-freighted mangoes in the wintertime, at more than 150 stores throughout the U.S. and a handful in Canada and the U.K.

Mackey, meanwhile, has emerged as both a hero and antihero of the environmental movement. On the one hand, he makes no apologies for running a large, consolidated operation that imports produce and displaces local farmers and small vendors. A notorious foe of unions, he’s a staunch libertarian described by The New York Times Magazine as a man “who admires Ronald Reagan and prefers The Wall Street Journal editorial page to this newspaper’s.”

On the other hand, nobody can dispute that Mackey led the fight to put organic on the mainstream map and make it more available to average folks. He’s placed a cap on executive compensation — his own included — and prefers to take a longer view of financial health than the quarterly model favored in the corporate world, to accommodate forward-thinking projects like humane animal-treatment standards, which he recently introduced.

Mackey spoke with Grist from the Whole Foods headquarters in Austin, Texas, about the pleasures of eating, his business philosophy, and the strategy that could build Whole Foods into a $30 billion monolith by 2020.

Whole Foods is the first major grocery chain to adopt a humane treatment standard. What does this mean technically? How do these standards work?

After dialoguing with a few animal-welfare and animal-rights groups — PETA [People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals], VITA, Animal Rights International, and Animal Welfare Institute — we decided that our existing standards for humane animal treatment were not rigorous enough. We began a process of working with these groups and our producers to develop standards species by species. We finished duck standards, and now we’re finishing up pig standards, and then from there we move on to lamb. And after lamb it will probably be beef. It’s a slow process because it’s highly participatory. We typically have in a meeting 20 people, which includes Whole Foods people, animal-rights group people, animal experts, and the farmers that we do our business with. I’m actually going to the meetings.

Can you give us some examples of those standards? What kind of treatment do they stipulate?

Let’s take ducks, for example. I mean, this may seem sort of obvious, but no ducks are raised like this now in America on commercial farms: The ducks will have access to the outdoors — meaning sunshine and fresh air — instead of being raised completely inside their entire lives. The ducks will have access to water to swim in; ducks have got to be able to swim. There have to be ways for the water to be cleaned, so you have to have standards for water cleanliness. The ducks need to have an enriched environment where they can forage for duck food. In factory farms or commercial animal raising, feeding is an entirely automated process with food pellets, but a lot of the satisfaction of an animal’s life is actually hunting for food. There will be no mutilations. Most livestock animals are mutilated when they’re doing intensive living, and they have their beaks partially cut off and their toes amputated without any type of anesthesia. We’re forbidding that.

How much more expensive is it to follow these humane standards?

Everybody is asking us that, but we won’t know until it’s done. Getting our farmers to produce to those standards means they have to retool their production facilities for us, so we don’t exactly know how much more it’s going to cost.

Will you change your standards based on bottom-line concerns?

I think one of the most misunderstood things about business in America is that people are either doing things for altruistic reasons or they are greedy and selfish, just after profit. That type of dichotomy portrays a false image of business. It certainly is a false image of Whole Foods. The whole idea is to do both: The animals have to flourish, but in such a way that it’ll be cheap enough for the customers to buy it.

Do you hope your move will put pressure on other grocers and meat producers to adopt more humane standards?

Yes. It’s my belief that most of Americans are in denial about factory farms in America. They don’t want to know what’s happening. They don’t want to look, because they’re not willing to give up meat. And it’s my belief that once we can really have animal-compassionate alternatives where people can buy this product and know that the animal was well-treated during its lifetime, that then they’ll be willing to look at what the factory farm is all about. I think when that happens, across the United States, there’s going to be outrage about factory farms.

When did you decide to become a vegan?

I’ve been a vegan now for a little over a year. And it’s not that big of a shift from vegetarianism; I mean, mostly it’s giving up dairy products. Technically, I am not a pure vegan because I eat eggs from my own chickens. My wife and I own a place outside of Austin and we have about 30 chickens out there, free-range, organic feed, extremely well-treated from their birth to their eventual death through natural causes. I don’t have any problems eating those eggs, but it’s the only egg I eat. But otherwise I’m a vegan, including clothing and products as well.

A few of the meat-free treats at Whole Foods.

As I studied and read the books, my consciousness was raised about how animals were treated. I became a vegan and at the same time I realized, gosh, Whole Foods has got to create a higher standard here. I think it will ultimately be a good business decision because I think our customers expect us, want us to pave this path.

Do you wish that Whole Foods didn’t offer meat at all?

That’s kind of like asking do I wish everybody lived exactly the way I live personally. Do I wish people didn’t eat sugar, do I wish people weren’t alcoholic, do I wish they didn’t smoke cigarettes, do I wish they didn’t drink coffee? Do I have some kind of religious faith that I want to convert everybody to or a political ideology that I expect everybody to adhere to? I believe people have got to make these decisions for themselves.

Sure, I wish Whole Foods didn’t sell animal products, but the fact of the matter is that the population of vegetarians in America is like 5 percent, and vegans are like 25 or 30 percent of the vegetarians. So if we were to become a vegan store, we’d go out of business, we’d cease to exist. And that wouldn’t be good for the animals, for our customers, our employees, our stockholders, or anybody else. If I were to take Whole Foods in this direction I would be removed as CEO.

Are there sustainable measures that you wish you could implement, but can’t because of practical bottom-line concerns?

First of all, I want to correct your thinking about this. We don’t think there is a contrast between sustainable or ethical issues and bottom-line issues. I want you to understand how we think about it. For us, our most important stakeholder is not our stockholders, it is our customers. We’re in business to serve the needs and desires of our core customer base. So take this example: What if we only sold organic stuff? We’d also cease to exist because not enough of our customers want us to just sell organic. They would find that it would be too expensive for them; they wouldn’t be willing to buy it. So we sell as much organic as we can, and we sell a heck of a lot more organic now than we did, say, five years ago. But if organic was to go the other direction, and people were to decide it was a hoax and stopped buying it, we’d stop selling it.

Wouldn’t you describe that as a tradeoff?

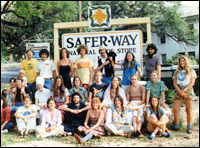

The Safer Way crew: Mackey is in the back row, fourth from the left, with the ‘fro.

If you speak to the totally pure, you will cease to exist as a business. I made these decisions 25 years ago. I mean, my first store was a little tiny store called Safer Way. I opened it in 1978. It was a vegetarian store. And we did $300,000 in sales the first year. And when we made the decision to open a bigger store, we made a decision to sell products that I didn’t think were healthy for people — meat, seafood, beer, wine, coffee. We didn’t think they were particularly healthy products, but we were a whole food store, not a “holy food” store. We’re in business not to fulfill some type of ideology, but to service our customers.

We’ve seen the health-food and organics industry grow roughly 20 percent per year for the last decade or so. What do you attribute to this groundswell in demand?

I think that there’s a movement in our society toward higher quality, and you see that not just in food but with Starbucks, people willing to pay more for coffee. You see it in automobiles, clothing, housing. America is becoming richer and richer, collectively. As people become wealthier they are willing to improve the quality of their life. And I’ve always argued that food and eating, collectively, is the greatest source of pleasure that you have over your lifetime. Eating is intensely pleasurable, it very much affects how we feel, our life and happiness and pleasure and longevity.

What has been lost in terms of the integrity of the organic and natural-food business during the rapid industry growth?

If anything, there’s been integrity gained because standards have become nationalized with the National Organic Standards Act being passed. You do have a lot more big business getting into it, but that has been part of the standards-building process, and so far I don’t think there’s been any real compromise in the quality of the products.

What about the question of consolidation: Once you become a big business, do you put local producers, local farms out of business and destroy local food webs?

Consolidation occurs in every industry as it grows, because customers always want prices to be lower. There’s a direct relationship between the scale of an organization and its ability to offer lower prices. It’s no accident Wal-Mart sells a lot of stuff really cheap — that comes along with being really large. But we put the customers first, and we are increasing the number of local products available in our stores because there is a strong customer demand for it.

Catering to those demanding yuppies.

There are two trends going on that are almost opposite trends. On the one hand you have this trend toward local products, people wanting more and more stuff that’s produced locally. And yet there’s also the trend for international ethnic foods, where people want to eat Thai food, and they want to eat Indian food, and they want to eat Mexican and Chinese and Ethiopian. And so we’re bringing in foods from all around the world. They may want a goat cheese that’s produced locally some of the time, and then they might want a really high-quality French brie. Some of the customers who most cry out for localization also like globalization.

What do you think of the USDA organic standards? Do you think they’re strict enough?

We’re proud of those standards because we participated in creating them. I think that we stood tough and kept out a lot of the agribusiness dilution that wanted to put GMOs in the standards and allow sewage sludge to be used as fertilizer.

The Bush administration tried to weaken organic standards. Do you have concerns about the Bush administration’s environmental policies?

Whole Foods is not going to take a stand on Bush administration policies. I voted for the Libertarian candidate, so I didn’t vote for either Kerry or Bush or Nader.

How from a political standpoint do you reconcile strict environmental protections with your libertarian beliefs?

As a libertarian, I’m not opposed to all government. I support what are the legitimate functions of government, and I believe environmental protection is one of the most important jobs government has.

You’re admired for placing a cap on your executive compensation and for having a salary that’s much lower than what it could be. And you prefer to take a longer view rather than estimate your corporate earnings according to quarterly results. What are some of the other unorthodox practices that you’ve put into place that you are most proud of?

Whole Foods is very committed to the team structure and self-managing work teams; they’re like the basic cells of the company. The teams are empowered. They do their own hiring. They do their own scheduling. To become a team member at Whole Foods, you have to get voted on by your team after a trial period. If you don’t get a two-thirds vote, you don’t get on the team.

Then there’s our concept of gain sharing: As productivity increases, then all the people at our stores make more money. It doesn’t flow down the bottom line, it flows into higher paychecks. Last year in gain-sharing we gave away close to $30 million. And stock options: We have a stock-options program that is not only for the executives of the company, but it’s wide-based; 94 percent of our stock options are given away to the non-executives in the company each year.

You get a lot of criticism for preventing unions from organizing your workers. Are these sort of employee-friendly processes ones that you really couldn’t implement with unions?

They’d be much more difficult to implement with unions. First of all, it’s a lie that Whole Foods somehow prevents unions from organizing. That’s against the law. We can’t prevent anybody from organizing a union; if our team members want a union, we can’t stop them. Our team members can have unions, but they don’t want unions because they create this adversarial relationship in the workplace.

One of the myths that unions will often talk about is that you could make a lot more money if top brass weren’t so greedy and taking in profits. But if you got rid of all the profits at Whole Foods, it would hurt the workers. The team members are already getting 24 percent of the total pie. For every dollar that comes into sales at Whole Foods Market, 24.1 percent is going out to our team members in wages and benefits.

Who are your heroes or inspirations in terms of your management vision and environmental vision?

I don’t know who my heroes are.

Looking into the future, what would be a worst- and best-case scenario for Whole Foods and the health-food industry?

Well, the worst-case scenario is we’ll be bankrupt and out of business. We set an official internal goal in 2000 to be a $10 billion company by the end of the decade. We’re growing at about a 15 to 20 percent clip, and we’ll be close to $4 billion this year, so if we continue to do that, and you look ahead 20 years, we’ll be $30 billion probably.

Will you focus your growth mainly on domestic markets?

We’ve begun our international expansion. We have a store open in Canada, and two more in development. We bought a seven-store chain in the U.K., and we are looking to do big stores in the U.K., and then, hopefully, we do intend to expand into Europe. So, we’re just starting in that direction, but 10, 15, 20 years from now, I expect that we’ll have a sizable market position in Europe. I think potentially Whole Foods can be a global company. We’ll see what the future brings.