Basket case: Annie Novak prepares to harvest some of Eagle Street Farm’s bounty.Photo: Yann Mabille

Basket case: Annie Novak prepares to harvest some of Eagle Street Farm’s bounty.Photo: Yann Mabille

In our New Agtivist interviews, we talk to people who are working to change this country’s f’ed-up food system in inspiring ways. For the next few weeks, as part of the Feeding the City series, we’ll be focusing on urban agtivists.

Urban farmer Annie Novak is on a mission to inspire New Yorkers to grow, cook, and eat good food — and to nurture the relationships that make it all possible.

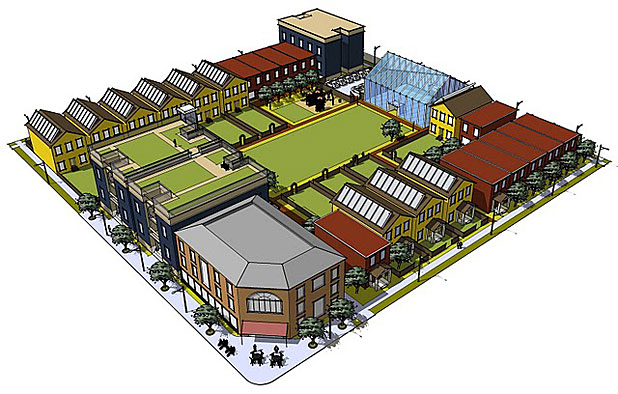

Born in Chicago, she is the oldest daughter of an artist mother and a father who worked for the Chicago Board of Trade, where he dealt with corn and soybean futures in the marketplace. After college, farming became central for Novak, 27, who is now a passionate advocate for sustainable practices. She helped start Eagle Street Rooftop Farm in Brooklyn, New York — a test farm utilizing green roofing materials for growing vegetables. In its second growing season, the farm has become a center of community, with a weekly market, a popular volunteer program, and farm talks on subjects like composting, artisanal food businesses, and chicken-raising. It has also already inspired similar projects. (See Grist’s previous coverage.)

Somehow, Novak finds time to run an education program she also cofounded, called Growing Chefs and work as the Children’s Gardening Program Coordinator at the New York Botanical Gardens. She participates in triathlons, and can be seen zipping around town on a bike that she built herself.

I spoke with her recently about her passions for growing food in the city and community organizing.

Q. Have you sown seeds in all five boroughs?

A. Almost. I’ve composted in Staten Island, but I haven’t planted anything there yet.

Q. How did you first get into farming?

A. When I was an undergraduate in New York, I went to Ghana. I was working [with chocolate farmers there], and I realized that I had no idea how chocolate grew, and that many of the cacao farmers had never had chocolate bars. That disconnect made me realize how far apart we are from our food.

Right when I graduated college, my father passed away. Everyone in my family — we’re all women — was faced with this moment of truth about our own choices moving forward and how we were going to provide for ourselves. Shortly thereafter, I started at the New York Botanical Gardens working in the children’s education department, teaching kids how to grow food. I decided that [USDA Plant Hardiness] Zone Six was the best growing climate, because you can grow tomatoes and kale. So after I’d finished the summer season, I moved upstate to begin farming in a series of apprenticeships. In the winter, I would choose crops that I was interested in and then go to the country I thought grew them best, to meet farmers at the market and negotiate a work exchange.

Q. What led you to farm in the city?

A. A big reason I like to grow food is to share it. Also, I like the idea that New Yorkers are so well-educated on one side of the spectrum of food. But, like when I was studying chocolate, and I would go on and on about the taste, and the cacao farmer would say to me “No, this is a treat,” I feel like it’s sort of my role here to say “Pay attention, this is a carrot.” Meaning all food, as a plant or organism, has its own history and ecological importance besides being delicious.

Q. How did Eagle Street Rooftop Farm get started?

A. The farm was the brainstorming product of Goode Green, a green-roof installation company here in New York, and Broadway Stages, a production company and the building owner. I came on board as a farmer. In New York City, we have many issues with storm water runoff, and Broadway Stages has access to many warehouses with flat roofs as well as a history of community support and involvement, so it was this perfect trial space to put up a green-roof vegetable farm.

‘Can the city feed itself? Maybe, but do you want the city to feed itself? I don’t think so. Having the consumer protection of upstate land is one of the most important things the city can do for the state.’

Q. Are there unique challenges to growing on a rooftop?

A. In a very literal sense, it’s unique because it’s on a roof and the layer of growing medium is very shallow. But you can actually still grow a lot of plants. For me, what was so interesting is that this is a really great way to connect with people directly about where their food comes from. Although it’s a lot less land than I’ve ever worked on, it’s certainly more involved than any other place I’ve farmed.

Q. You’ve said that you see the farming you’re doing in the city as directly supporting the farmers in upstate New York. How so?

A. In just one example, I run a Community Supported Agriculture program that only offers half-shares. One of my members told me that they belong to another CSA that’s based upstate. That’s exactly what I wanted. The quality of our air and water is protected by upstate organic growers. Can the city feed itself? Maybe, but do you want the city to feed itself? I don’t think so. Having the consumer protection of upstate land is one of the most important things the city can do for the state.

Q. What advice do you have for someone thinking of a career in farming?

Kale to the queen: Annie Novak at Eagle Street Farm in Brooklyn.Photo: Yann MabilleA. Learn everything you can, from books and those older and more practiced. You work hard, and that is the most difficult and the most rewarding thing about it. This year, we’ve had one of the hottest summers that I’ve ever experienced. It’s been devastating to watch what that does to the plants. At the same time, the beauty of agriculture is that it comes in cycles. It gives you a real patience. That consciousness hopefully makes you a better environmental steward, because you have that long-term sensibility. How different that is from the way technology asks us to think today, with such immediate demands.

Kale to the queen: Annie Novak at Eagle Street Farm in Brooklyn.Photo: Yann MabilleA. Learn everything you can, from books and those older and more practiced. You work hard, and that is the most difficult and the most rewarding thing about it. This year, we’ve had one of the hottest summers that I’ve ever experienced. It’s been devastating to watch what that does to the plants. At the same time, the beauty of agriculture is that it comes in cycles. It gives you a real patience. That consciousness hopefully makes you a better environmental steward, because you have that long-term sensibility. How different that is from the way technology asks us to think today, with such immediate demands.

Q. Tell me about Growing Chefs, the organization you started.

A. Growing Chefs is a team of nutritionists, chefs, green thumbs, and educators dedicated to the simple premise of teaching eaters of all ages how to grow and eat good food, from field to fork. The organization started with my own curiosity for food narratives, and has since expanded to include all manner of programming, including the work we d

o on the Rooftop Farm. We keep a pretty simple philosophy: Broccoli is not boring!

Q. Have you always been interested in food?

A. Food was not a huge part of the way in which we were brought up. When I tried Thai food for the first time as an undergrad, I remember thinking how incredible it is to have the opportunity to be so creative with food every single day.

Q. To whom do you look for inspiration?

A. My hero has always been Mr. Wendell Berry. But what’s really lucky about this kind of work is that farming is built for apprenticeships — you can work alongside the people who are your heroes. I am excited about people like First Lady Michelle Obama, who is helping generate so much enthusiasm about growing healthy food.

Q. Are there books to which you keep returning for guidance?

A. There’s a book called Start with the Soil — it’s actually sort of a technical book. Also, Wes Jackson is amazing. He is doing his best to pull the Midwest back to its former fertility. Of course, Wendell Berry, again and again. I just re-read Murray Bookchin’s writing on social ecology; it’s nice to know that there is a bigger picture outside of the everyday work that I face.

There’s been so much beautiful work written about farming. It’s wonderful because the work itself is so hard and so frustrating, but so many people are willing to over-romanticize it. Reading can sometimes be the metaphorical aloe vera for your literal sunburn!

Q. Do you have a junk food weakness?

A. [Laughs] Yeah! Alas, I love anything that combines peanuts and chocolate.

Q. Company drops by unexpectedly around dinnertime. What do you feed them?

A. You know, whatever happens to be on the countertop. I’m a really simple chef. I like to take three ingredients and make a meal, because with good produce there is not a lot you need to do.

Q. What keeps you up at night?

A. Weather. I say that when I raise children this will change, but right now I spend all night worrying if my plants are okay. The chickens, too.

Q. You like to barter for goods and services. Could you talk a little bit about that?

A. One of the good things about working in agriculture is that there is a lot of giving. Barter becomes one of those simple things that you build into your life. It means that money is not the only way that you communicate with people — actual values are. Bartering can become part of the foundation for building honest relationships.

Q. Anything you’d like to add?

A. People often want to know where this sensibility comes from, this love of farming. For me, I loved chocolate, and now I have boundless curiosity for worms and carrots. But it’s different for everyone. Everyone has different passions. If you can’t see yourself farming, or you can’t imagine taking the time to barter, at least hold true to the simple premise that it’s important to be good to people. The culture of agriculture ties all that together, but it’s something everyone’s life should have.