The USDA says to eat more of this stuff.Every five years, the USDA formulates new dietary guidelines — advice for Americans on what to eat. And every five years, the guidelines are greeted with a chorus of derision. Critics like Michael Pollan and Marion Nestle have long argued that the agency backs away from directly challenging the food industry — instead of focusing on actual food, the agency fixates on the vague concept of nutrients. For example, rather than “eat less meat,” the agency has been more inclined to trot out abstractions like, “reduce consumption of saturated fat.”

The USDA says to eat more of this stuff.Every five years, the USDA formulates new dietary guidelines — advice for Americans on what to eat. And every five years, the guidelines are greeted with a chorus of derision. Critics like Michael Pollan and Marion Nestle have long argued that the agency backs away from directly challenging the food industry — instead of focusing on actual food, the agency fixates on the vague concept of nutrients. For example, rather than “eat less meat,” the agency has been more inclined to trot out abstractions like, “reduce consumption of saturated fat.”

In that context, the new “Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010,” seems remarkable — even courageous — in its blunt discussion of plant-based diets.

The new edition has a fascinating chapter on eating patterns, focusing on real foods and not just nutrients. This chapter on eating patterns provides a nice counterpoint to the reductionism — what Michael Pollan calls “nutritionism” — of scientific discussion of diet and health. The guidelines’ healthy eating patterns may or may not include meat. For example, the USDA Food Patterns and the DASH diet each include moderate amounts of meat and plenty of low-fat dairy. At the same time, the guidelines explain clearly that meat is not essential, and near-vegetarian and vegetarian diets are adequate and even “have been associated with improved health outcomes.”

In reviewing the scientific evidence on vegetarian diets, the guidelines say:

In prospective studies of adults, compared to non-vegetarian eating patterns, vegetarian-style eating patterns have been associated with improved health outcomes-lower levels of obesity, a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease, and lower total mortality. Several clinical trials have documented that vegetarian eating patterns lower blood pressure. On average, vegetarians consume a lower proportion of calories from fat (particularly saturated fatty acids); fewer overall calories; and more fiber, potassium, and vitamin C than do non-vegetarians. Vegetarians generally have a lower body mass index. These characteristics and other lifestyle factors associated with a vegetarian diet may contribute to the positive health outcomes that have been identified among vegetarians.

The new guidelines have adapted to many of the scientific criticisms of earlier editions. For example, Harvard scientist Walter Willett has long argued that replacing saturated fats with unsaturated fats saves lives, and that refined grains and simple carbohydrates are no healthier than unsaturated fats. The new Dietary Guidelines seem to me to be in complete agreement.

However, not everybody likes the new guidelines. The most vociferous low-carb advocates say it is wrong to criticize consumption of saturated fats. Just this week on the Civil Eats blog (cross-posted on Grist), Kristin Wartman tore into the conventional wisdom on saturated fats: “The notion that saturated fats are detrimental to our health is deeply embedded in our Zeitgeist — but shockingly, the opposite just might be true.” I generally agree with the way low-carb advocates criticize sugar and simple carbohydrates, but this corollary view of saturated fats worries me. Wartman’s view seems threatening to the guidelines’ favorable perspective on near-vegetarian and vegetarian diets, which are typically lower in saturated fats.

Because the saturated-fat corollary to the low-carb criticism of the Dietary Guidelines is widely believed, I need to spend a couple more paragraphs on why a low-saturated-fat diet might be okay for your health.

First, there is the scientific evidence that lowering saturated fat reduces risk of heart disease. If you are primed to disbelieve any reductionist arguments, you can ignore this paragraph. But what strikes me as a lay reader of the scientific literature is how systematic and transparent the Dietary Guidelines’ evidence reviews now are. For saturated fats, you can see exactly what protocol was used to select studies for review, and what criteria were used to evaluate them. You can confirm that the external “Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee Report” correctly reflected the evidence review, and that the actual Dietary Guidelines correctly reflected the advisory committee report. If you read any of the main low-carb advocates — such as Gary Taubes — see if you can discern in a similar way what his or her implicit protocol was for selecting studies to consider. If you find fault with the Dietary Guidelines’ evidence review, please send a link in the comments to any systematic and transparent evidence review that you find superior.

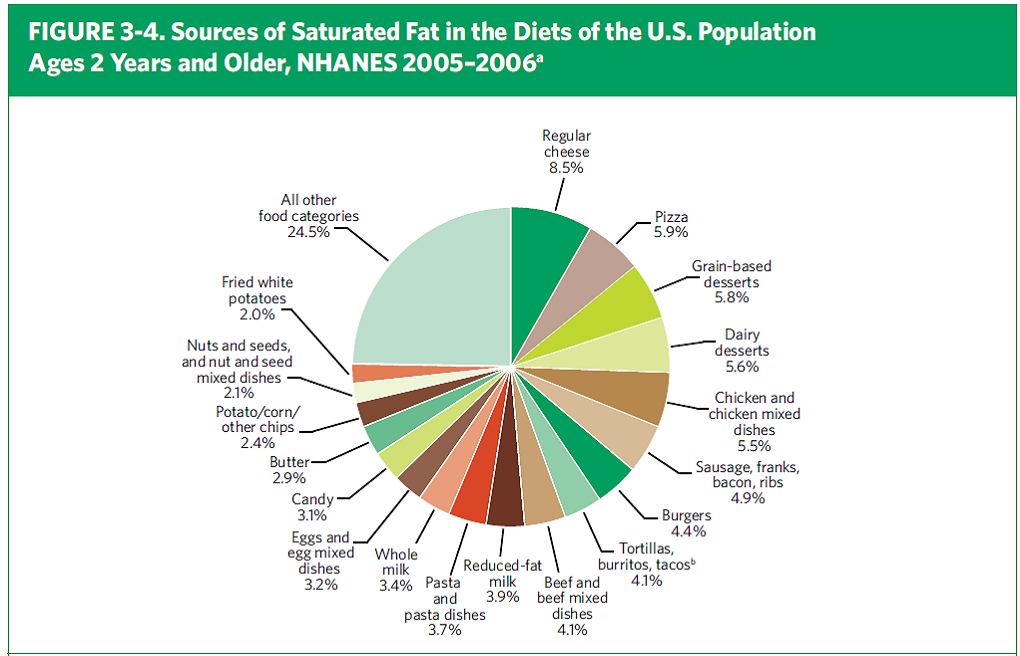

Second, there are the foods themselves that contain saturated fats. Part of the criticism of “nutritionism” is that USDA lacks the courage to criticize specific foods. The guidelines may criticize saturate fats, but they won’t mention specific foods, the critics say. I have my own slightly gentler expectation for the federal government’s frankness in reporting. If the guidelines use scientific jargon for a food component such as “saturated fats,” I think they should say what foods typically contain that component. This is exactly what the new edition does very well. Here is the new report’s pie chart to accompany the discussion of saturated fat:

So, the main implication of the Dietary Guidelines’ continued criticism of saturated fat is to recommend reducing some combination of: regular cheese, pizza, grain-based desserts, dairy desserts, chicken and mixed dishes, sausage, franks, bacon, ribs, burgers, and so forth. As long as we all agree that occasional treats in reasonable portions are harmless, this advice sounds just fine me. I don’t see why anybody would complain about the Dietary Guidelines on this point.