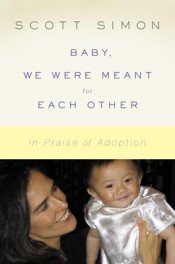

Scott Simon“I wish that people who want to become parents would consider adoption as a great way to have a family from the start, and not just a last resort,” writes Scott Simon in his new book Baby, We Were Meant for Each Other: In Praise of Adoption. Simon, host of NPR’s Weekend Edition Saturday, is father to two young girls adopted from China.

Scott Simon“I wish that people who want to become parents would consider adoption as a great way to have a family from the start, and not just a last resort,” writes Scott Simon in his new book Baby, We Were Meant for Each Other: In Praise of Adoption. Simon, host of NPR’s Weekend Edition Saturday, is father to two young girls adopted from China.

I thought the eco-conscious crowd would be a perfect audience for Simon’s book, so I got myself a copy and arranged to interview him.

I was surprised, then, when I sat down to read the book and came across this passage:

Adopting a child to prove something is not a healthy motivation. I would seriously consider alerting the authorities if I heard a prospective parent say, “We want to adopt because it’s the most environmentally responsible thing to do. Don’t want to increase our carbon footprint, after all!”

Has any environmentally concerned person ever chosen adoption in order to “prove something,” and what might that “something” be? I asked Simon about this when we sat down to talk in Seattle recently. But first we kicked off our conversation with general talk about adoption and his book.

—–

Q. In writing this book, do you want to encourage more people to consider adoption when they’re forming their families?

A. I don’t mind saying yes. I hope they’ll think of adoption not just as a last option. I’m a little ashamed to say that my wife and I, our reflex position when we accepted that we couldn’t naturally conceive like Abraham and Sarah was not adoption. We went through a couple rounds of assisted fertility, which didn’t work. We made a decision after those rounds that this is ridiculous — there are children in the world already who need us, so why don’t we do that?

Q. What challenges do adoptive parents face?

Q. What challenges do adoptive parents face?

A. You want to be sensitive to the ways in which your child may need special attention because of the way they began life — the months they spent in institutions, where they didn’t receive the sort of intimate nurturing you would like to think every child in the world could have. And yet you don’t want to make that into some kind of trauma or infirmity or trace everything back to that.

Q. What sort of support systems have you discovered for parents with adopted children?

A. We have seen a very good family therapist, where we can come together and talk about getting along. It’s not a sign of weakness, any more than going to the dentist is.

Until recently, [our daughters] were going to a weekly cultural class. We call it Chinese class — it’s Mandarin and stories and songs.

Q. Are there good things that have come about through adoption that you didn’t expect?

A. I think in some other families — like the one I grew up in — you assume a lot. “Oh, my son, of course he knows I love him.” I think with adoption, you’re inspired to talk about this kind of stuff out loud, lift the hood on the engine a little bit, talk about how important you are to each other. That’s been wonderful.

Q. People like Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt and Madonna have made international adoption seem trendy. Overall, do you think that’s had good or bad effects?

A. I think good. I don’t know if it’s had an effect in terms of statistics. It has opened a kind of window to adoption, put it into people’s minds. Brad and Angelina adopted before they had [biological] kids, and that’s an option too.

Q. It seems you don’t think environmental concerns are a legitimate reason to consider adoption.

A. I think I said in the book that I would call the authorities myself if somebody said, “I want to adopt because I want to reduce my carbon footprint.” Because I think you ought to have children out of joy, not out of sense of duty.

But that being said, there are 150 million orphaned and abandoned children in this world, and that’s the only chance at life they get. They deserve loving families. If somehow you could connect the number of people in this world who want to have children and more of the youngsters out there who could use families, that’s a kind of global warming we could all use.

I try to discourage the idea that adopting youngsters is a good thing to do the way giving to Oxfam is a good thing to do. But it is a good thing to do. It’s good for those of us who adopt. It’s transforming — literally, physically, emotionally transforming.

Coming back to the fact that you should be a parent joyfully — you shouldn’t say, “Well, we want to have children, but I just can’t stand bringing another child into the world when there’s so many already, and I want to reduce our carbon footprint.” But if on the other hand you want to have a family, and you say, “Gosh, there’s so many children in the world, why don’t we adopt?” — that I think is good. That’s out of joy.

Q. You make the point in your book that no one adopts by accident. Obviously, anybody, no matter what their reason, is doing it because they want to be a parent. I don’t think anybody would adopt to prove a point.

A. No, I certainly hope not.

Q. But those are your words in the book.

A. And I can’t say I’ve ever run into anybody who’s ever said that.

I’m not trying to stand in judgment. I don’t regret the two rounds of assisted fertility my wife and I went through, in the sense that we learned something from it. But we’ve known people who have gone through so many rounds of assisted fertility, and that just strikes me as utterly useless when there are already children in the world. I have talked to people who have said, “I would have loved to adopt, but I couldn’t qualify, so we went to an assisted facility,” and that I understand. But I hope our story and the story of others will get people to consider there are already children in the world.

Q. I work for an environmental publication, and I’ve been writing lately about my choice not to have children, which I didn’t make for environmental reasons — I just don’t think it’s right for me. But it’s been stimulating dialogue about different ways of living, different ways of forming families.

A. When we make a decision like that, it’s not always permanent.

Q. No. I reserve the right to change my mind, but I don’t expect to.

A. And you shouldn’t feel like there’s any pressure to do that. I think when I was 30 I might’ve said the same thing, and then I felt profoundly different. I talk to people in the book who say they have no interest whatsoever in meeting their birth parents, and I think it’s possible that five months or five years or 10 years after saying

that, they may feel differently. There’s a plotline on Grey’s Anatomy about that right now. Or, forgive me, if you meet someone.

Q. Anyway, I got some requests from people who are concerned about environmental issues and wanted to hear about adoption as a potential option — people who want to be parents but are concerned about leaving the world in a livable condition for the next generation. So that passage in your book struck me as really judgmental and unfair to people who are concerned about environmental issues and who might want to consider adoption.

A. I’m sorry if it sounded judgmental. There’s a thin line in a book like this where you reach conclusions out of your own experience. Obviously they should make their own judgments. Having children is a profoundly personal decision and personal experience, and I can’t put myself in the position of judging. I keep getting back to the fact that I think for all kinds of different reasons, [adoption is] a very good thing to do.

That being said, anybody who has children should do it out of a sense of joy, not out of a sense of duty. That doesn’t come to the exclusion of also wanting to be a responsible citizen of the planet.

Q. I think it can be a joyful decision to want to be working toward a better world for your kids and want to have kids. I question the notion that it’s somehow not joyful to want to live your values as you create your family.

A. I think that’s a better way of putting it. If that’s who you are, that embodies your values, then of course. I guess I’d be concerned about people that just decide that’s the factor that will send them to do it. Although, this being said here, I’m trying to be aware of my own contradictions. I don’t recall my exact words, but I don’t mean to insult anybody else’s moral position.

Q. Ironically, your happy family came about through the unhappy circumstance of China’s draconian one-child policy. How do you reconcile that in your mind?

A. What we tell ourselves — and it’s not just to reassure ourselves, it’s the absolute truth — is that we did not get our children from a family or a single mother; we got them out of institutions. If we hadn’t adopted them, or somebody else hadn’t adopted them, they would’ve grown up in institutions. They wouldn’t have grown up in institutions in the way that we understand growing up — they would have stayed there until the age of 12 or 13, then they would’ve gone into farm or factory work, or worse, which is too terrible to contemplate. It’s China’s one-child policy that took them away from their families. I don’t think anything would’ve been accomplished by leaving them there. I say a few times in the book, it’s our blessing that began with a tragedy, a tragedy that’s also a crime.

It’s also not as if my wife and I decided we found China’s one-child policy so reprehensible that we decided we were going to get one and then two daughters from there. [We did it] for a lot of different reasons, up to and including falling in love with Chinatown in New York. You look for signs.

We have adopted two girls who are Chinese; we are a half-Chinese family now. In a way, we feel much more obliged to inform ourselves about what’s going on in China, and explicitly with state planning of family policies, than we probably did before we adopted our daughters from China, because this is part of our family now, it’s part of our heritage too.

Q. Anything else you’d like to add?

A. I find it odd that we have so many new technologies for having families now, and adoption is as ancient as childbirth. I would not want some of the new technologies to come at the expense of adoption. Children who need families are a great potential blessing in so many lives, and that’s what I hope people will open their eyes to.

—–

Watch Simon being interviewed about his book by his daughter Elise: