This weekend, I wrote a somewhat abstract post about how America’s built spaces prevent many Americans from connecting with the supportive social networks essential to health and happiness. Let’s zoom from the lofty down to the concrete. Let’s talk about my neighborhood.

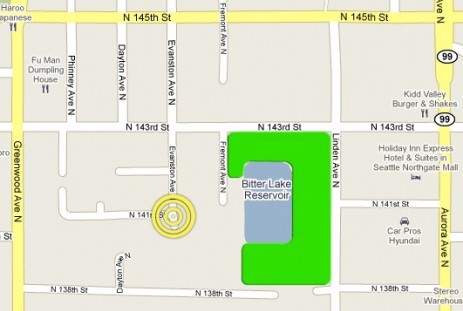

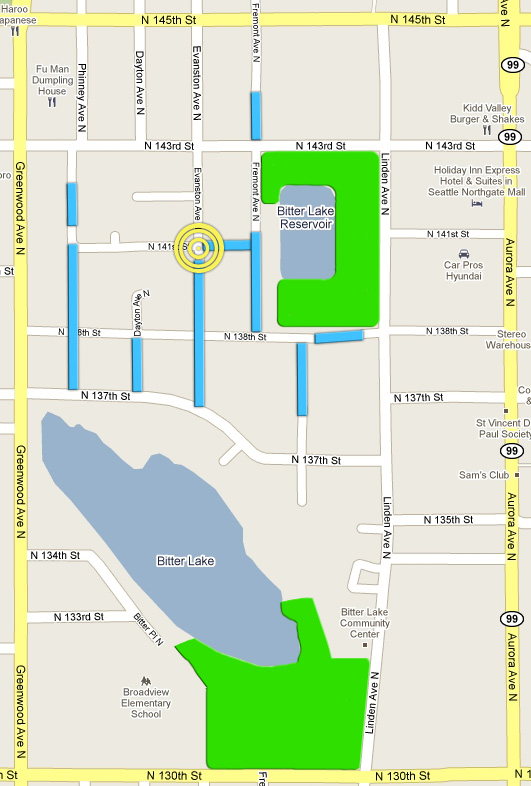

I live in the Bitter Lake area of Seattle. (In the early 20th century, an adjacent sawmill dumped so much tannic acid into the lake that horses wouldn’t drink the water — thus the name.) It’s zoned as an “urban village,” but at least for now that designation is, er, aspirational. Most of it isn’t mixed use, but it’s not quite suburban. I guess it’s one of those “inner-ring suburbs” you hear about. It was developed in the 1950s-’70s. Here’s my bit (with current public space in green):

As you can see it’s a fairly discrete area, bounded on four sides by busy arterials. Inside those arterials, there’s no reason you couldn’t have a thriving community. It already has a decent walkability score. There are a couple of parks; Greenwood boasts several restaurants and cafes; Aurora has an array of big box retailers; there’s a great supermarket just a few blocks north of 145th. There are more people coming in, too, as a series of condos are built along Linden.

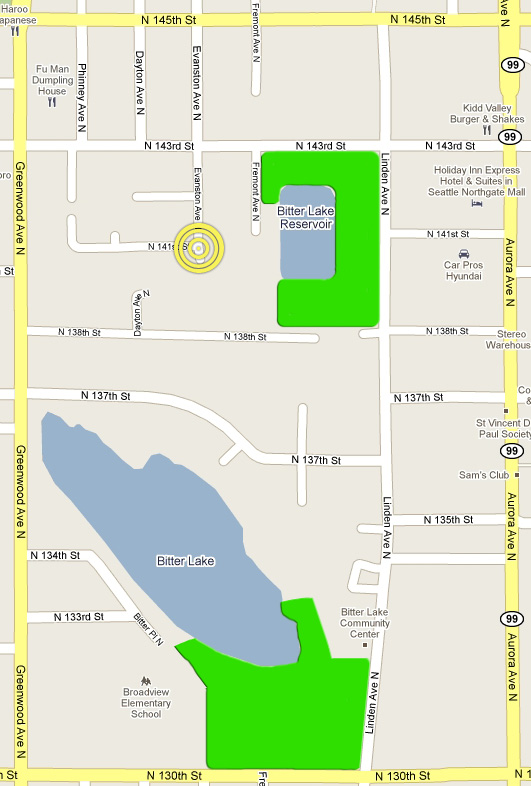

But despite all the ingredients … there is no such community. The first and primal cause is that there are no %*#! sidewalks. (You hear me Mayor McGinn? Show me what the new guy can do!) But I think the problems run deeper. Look closely at the map and you’ll note that the development pattern is almost aggressively misanthropic. Everyone is isolated from everyone else! For a simple illustration, consider how my kids and I walk to Bitter Lake park:

Today, we take the route in orange. The shorter blue route would require either a road or a footpath to cut through residential areas. Also, the north end of the lake is private, so the blue path would require opening up at least a stretch of it as public space.

Distance-wise, the orange path isn’t all that much longer than the blue, but it feels like it. It runs along fairly busy streets with only patchy bits of sidewalk (%*#!). Linden is still slightly skeevy; we’d be nervous about letting the kids walk it without us. The blue route would be through a peaceful, heavily wooded residential area, more safely walkable or bikeable.

The seemingly small difference between the blue and orange routes is enough to make a fairly large difference is our daily life: we just don’t go to the park much, and thus don’t interact with the other Bitter Lakers who spend time there.

Making connections

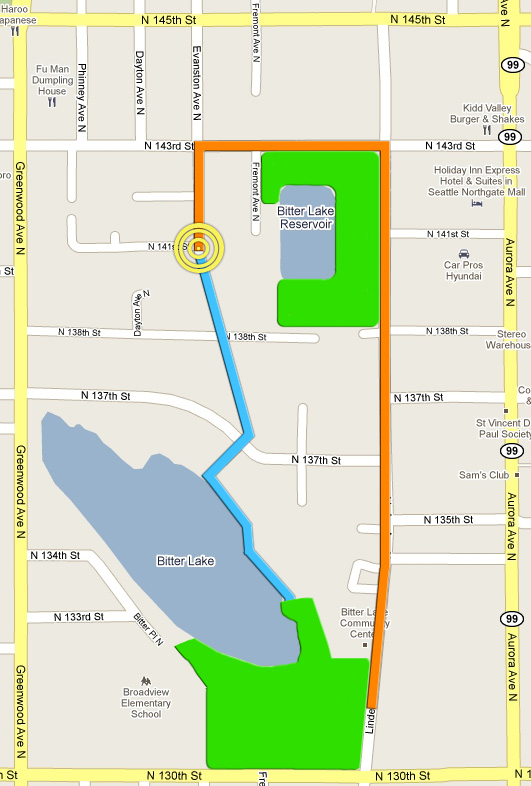

That’s just one example of a pervasive problem. For instance, look at 138th going from Greenwood to Aurora:

WTF? Presumably they wanted to avoid making it into an arterial (which is what happened to 143rd). One way would have been to connect it to the streets above and below it in a grid pattern, narrow it, and install traffic-calming features like traffic circles. Another way would be to … stick a random gap in it. Now the only people who ever see the western chunk of 138th are people who live on it, and they never see anyone else. It’s an impenetrable, neighborhood-dividing peninsula.

The map doesn’t show it well, but see that spur of Dayton Ave N that juts off 138th? The houses on that little cul de sac are within a stone’s throw of my place. There may be all sorts of groovy people living there, but we’ll never know, because to get there we have to go north to 143rd, west to Greenwood, south to 138th, and east to Dayton. Suffice to say: we wouldn’t do that unless we already knew someone there, and we’d never meet anyone there unless we did it. So we don’t.

Consider how the character of the neighborhood might be different if it were more of a grid (additions in blue):

With these new streets (or bike/footpaths), people on 143rd, 141st, 138th, and 137th would actually be part of the same neighborhood. They could have block parties.

I guess in the ’60s developers were in the grips of some pretty awful ideas about urban development. There was a love affair with cul-de-sacs and an effort to make almost every street in my area into one. Cul-de-sacs may feel safe, but their isolation from the surrounding neighborhood makes crime easier, not harder. They also make it difficult to walk anywhere, pushing people into cars, which prevent rather than facilitate spontaneous social interaction. By and large Seattle has turned against the cul de sac. (See also “The Cul-De-Sac Backlash” from Brad Plumer.) The thorny question is how to retrofit an area that’s already full of them.

Finding a center

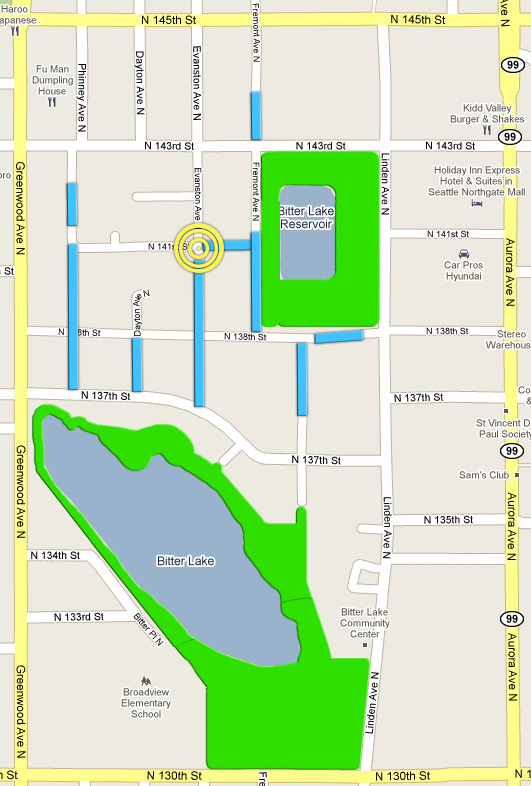

One more fantasy-world addition to my neighborhood. Right now, only the very southern tip of Bitter Lake is public space. The west, north, and east sides are lined with private docks and piers, which go mostly unused.

What if a strip around the entire lake were made into a park, along the lines of Green Lake park (about 60 blocks south)? There could be a nice walking/running/biking path, an area for a farmers market or food stalls, and plenty of greenspace. It could be accessed via Linden on the southeast, Greenwood on the west, or anywhere along the north end for residents of my neighborhood. Something like this, with public areas (including existing parks) in green:

Such a park would actually link the lake to the neighborhood above, offering everyone there a shared public space to walk, ride bikes, and congregate on a day to day basis. The park would also pull in people from outside the neighborhood and increase the property value of the entire area. (Have no fear: Linden is zoned to require a percentage of low-income housing.)

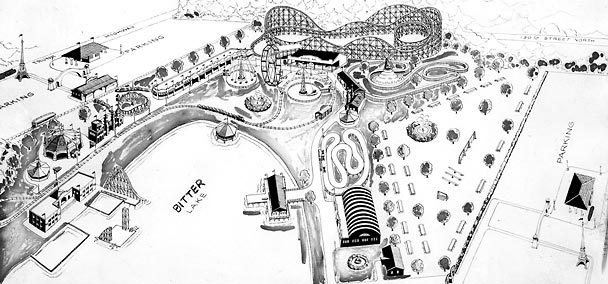

Interestingly, from 1930-1960, the entire south end of Bitter Lake was gathering place — an amusement park called Playland, served by a trolley (the Interurban) from Seattle:

Seattle Times archive

Seattle Times archiveWhat a shame that the lake went from famous attraction to grubby, forgotten urban pocket.

For me personally, a neighborhood like the one sketched above would mean that once my boys are a little older, I could send them out the front door on a Saturday afternoon and say, “Be back by dinner time.” I’d know there’s a bounded neighborhood for them to explore, with linked, diverse spaces filled with people they see them regularly, and who can keep an eye on them. It would mean a community.

Here’s the takeaway, for the few hearty souls still reading this logorrheic post: one of the biggest challenges in years ahead, as we attempt to densify and green our communities, will be retrofitting existing neighborhoods to increase walkability, sociability, sustainability, and safety. It’s worth a minute of anyone’s time to ponder how they could make their own surroundings more amenable to spontaneous, non-commercial, human-scale social interaction.

(And then after pondering and making blog posts with pretty pictures, it might even be worthwhile to start engaging with your local neighborhood groups and city council to get the slow, frustrating process of NIMBY-inhibited change underway. Here, for example, is the neighborhood plan for Bitter Lake, waiting around for funding. It looks cool!)