The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People celebrated its centennial last week by jumping into the policy debate over global warming. Delegates at the storied civil rights organization’s annual meeting in New York voted to adopt a resolution supporting clean energy development, curbs on greenhouse gas emissions, and policies to foster green collar jobs.

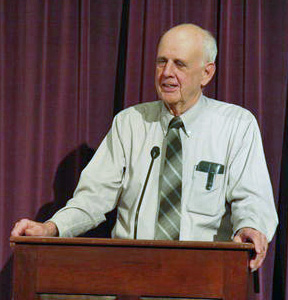

Dale Charles of NAACP’s Arkansas chapter was a leader in getting the climate change resolution approved by the civil rights organization.Photo courtesy Dale Charles“This is a policy that was passed unanimously at our convention,” said Hilary O. Shelton, the director of NAACP’s Washington, D.C., bureau.

Dale Charles of NAACP’s Arkansas chapter was a leader in getting the climate change resolution approved by the civil rights organization.Photo courtesy Dale Charles“This is a policy that was passed unanimously at our convention,” said Hilary O. Shelton, the director of NAACP’s Washington, D.C., bureau.

According to Shelton, the association will be making climate change policy a priority in coming weeks and months, at both the grassroots and federal levels. “With this new resolution, this gives us even more emphasis to push our units to be more actively engaged,” he said, by getting educated on the issues, meeting with legislators, writing op-eds for local newspapers, and more.

With about twice as many blacks as whites out of work across the nation, 25 percent of the nation’s 41 million blacks living below the poverty line, and 20 percent lacking health insurance, issues like rising energy costs, curbing air pollution, and creating green collar jobs are not abstract issues.

“African Americans have been disproportionately affected by pollution, from water, to toxic waste being dumped in our communities, to air quality,” said Dale Charles, president of the NAACP’s Arkansas chapter, whose Little Rock branch sponsored the climate change measure. “This resolution will help establish policies to eliminate or slow down that process of putting those types of elements in our environment, where our people have to live and our children have to breathe.”

NAACP is taking on global warming in partnership with the National Wildlife Federation. When it comes to climate change, this 73-year old, 4-million-member strong bastion of the mainstream environmental movement is better identified with polar bears stranded on melting icebergs than with communities of color fighting against air pollution, or for jobs programs.

But there’s no inherent contradiction in the alliance, said Marc C. Littlejohn, NWF’s manager of diversity partnerships. “Communities of color are normally, when it comes to global warming, the first and worst impacted.”

Colombia Law professor Ted Shaw noted that the NAACP is hardly new to tackling environmental issues. “The NAACP has been involved in environmental justice issues,” said Shaw, who litigated such cases during his 20-odd years with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, a separate but allied organization. “This is ratcheting [that] up.”

Judging from some of the coverage of last week’s convention in the mainstream media, there is a widespread debate that the NAACP’s political relevance may be fading. “A century ago, when the NAACP was founded, black America was under siege — lynchings were common, race riots had rocked major cities and Jim Crow segregation was being codified throughout the South. Today, all of that is fast-receding history,” wrote Eugene Robinson in The Washington Post. “Some critics have wondered whether there is still a role for an organization like the NAACP.”

Shaw said he thinks the association, which has a membership of just over half a million, can still have a lot of influence when it wants to.

“I think that the membership, the level of consciousness of the membership, is probably similar to the consciousness of most Americans” about global warming, he says. Some people think it’s a significant problem, and some people don’t. But “when the NAACP as an organization decides to make this priority,” says Shaw, “the rank and file members will have a much higher consciousness of it, and will get behind it.

“I’m not telling you that this is the 1960s, and it has the prominence it had in the civil rights movement,” Shaw said. “But it’s a group that periodically flexes its muscles — and it can be formidable.”

Dale Charles is confident that the association can have a big impact on climate legislation. “NAACP, through its hundred years of advocacy, our longstanding work in human rights and civil rights — we have a track record, the ability to mobilize people across the country and address certain issues and make our voices heard,” he said.

Charles would like to hear some raised voices when it comes to targeting federal recovery dollars to jobs for African Americans. “In my state we’re going to spend millions on highway construction,” he said. “We don’t have black firms big enough to bid on those projects. So none of that money is going to come back to the black community.”

Obama needs to wake up to this situation, said Charles. “Right now it seems to be that the same people who had control of the money before are going to have control of this money,” he said. “It’s not going to trickle down to Main Street the way Barack Obama intended. Green jobs won’t get to African Americans if business as usual continues.”

Shelton agreed. “When we talk about climate change, we also have to talk about how strategies, programs, and initiatives that are being implemented to address problems of climate change are also very sensitive to the issues of people who live on Back Street” but aspire to become solid middle class residents of Main Street. “Those are NAACP’s constituents,” he said.

Until people perceived the living-wage job opportunities inherent in transitioning to a low-carbon economy, said Shelton, conservation issues were often framed as having to give something up. “Are you going let a company come in that was going to pollute the air, pollute the ground, and probably pollute the water? But they’re going to bring 400 new jobs that pay a living wage? That was the framing: you sacrifice for a clean environment and don’t have jobs, or you have the jobs and sacrifice the environment?”

But now the solutions to climate change and to African-American poverty are coalescing. “Now, we can say yes to the creation of new forms of energy, jobs that maintain those new forms of energy, yes to clean air, yes to jobs that pay a fair wage and include health insurance,” Shelton said.

Green collar jobs will include manufacturing jobs in hybrid automobiles and renewable energy, as well as weatherizing homes and other skilled service professions, Littlejohn said. But equal priority must be given to cultivating new generations of black professionals, “getting college students to invest in jobs that are going to be more productive or innovative for clean energy: engineering, architecture and LEED certification.”

The NAACP’s resolution urges lawmakers “to ensure that the response to climate change can take a higher ground than business as usual – one that ensures that we capture real public benefits from the new energy economy.”

Given the iffy prospects for strong carbon-capping legislation in the Senate, the time has come for a more colorful grassroots climate coalition.

“I’m happy that this is not an issue that people will continue to see as one of these white liberal causes that doesn’t connect to their lives,” says Shaw. “Because this issue is connected to all of our lives. Climate change doesn’t know anything about segregation.”